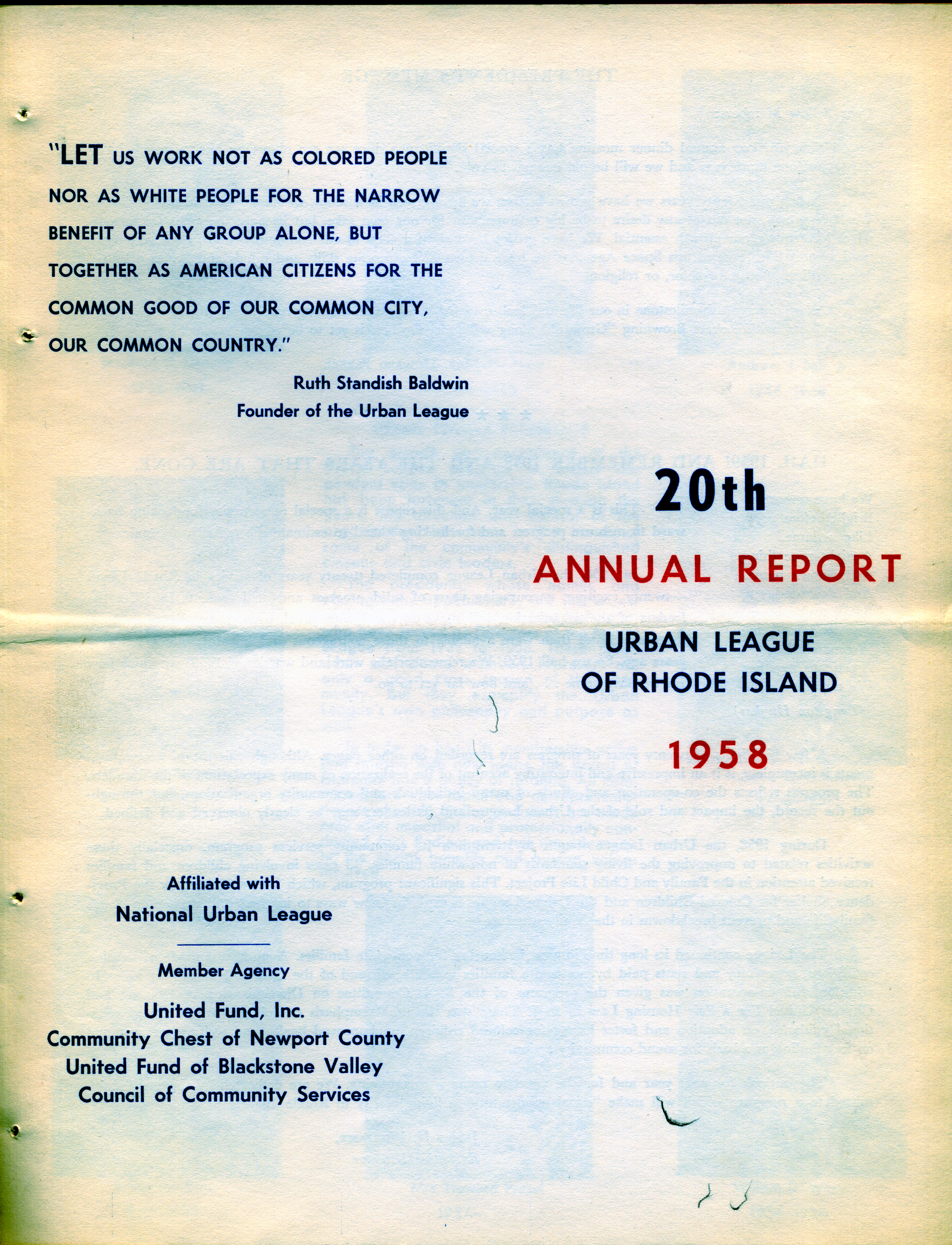

The Urban League’s annual report describes the achievements of the organization in the years leading up to the nationally tumultuous 1960s. Included in the report are a timeline of the League’s “significant events and activities” as well as the names and photographs of the League’s presidents, both black and white.

Read the full report here.

Courtesy of the Providence Public Library, Rhode Island Collection

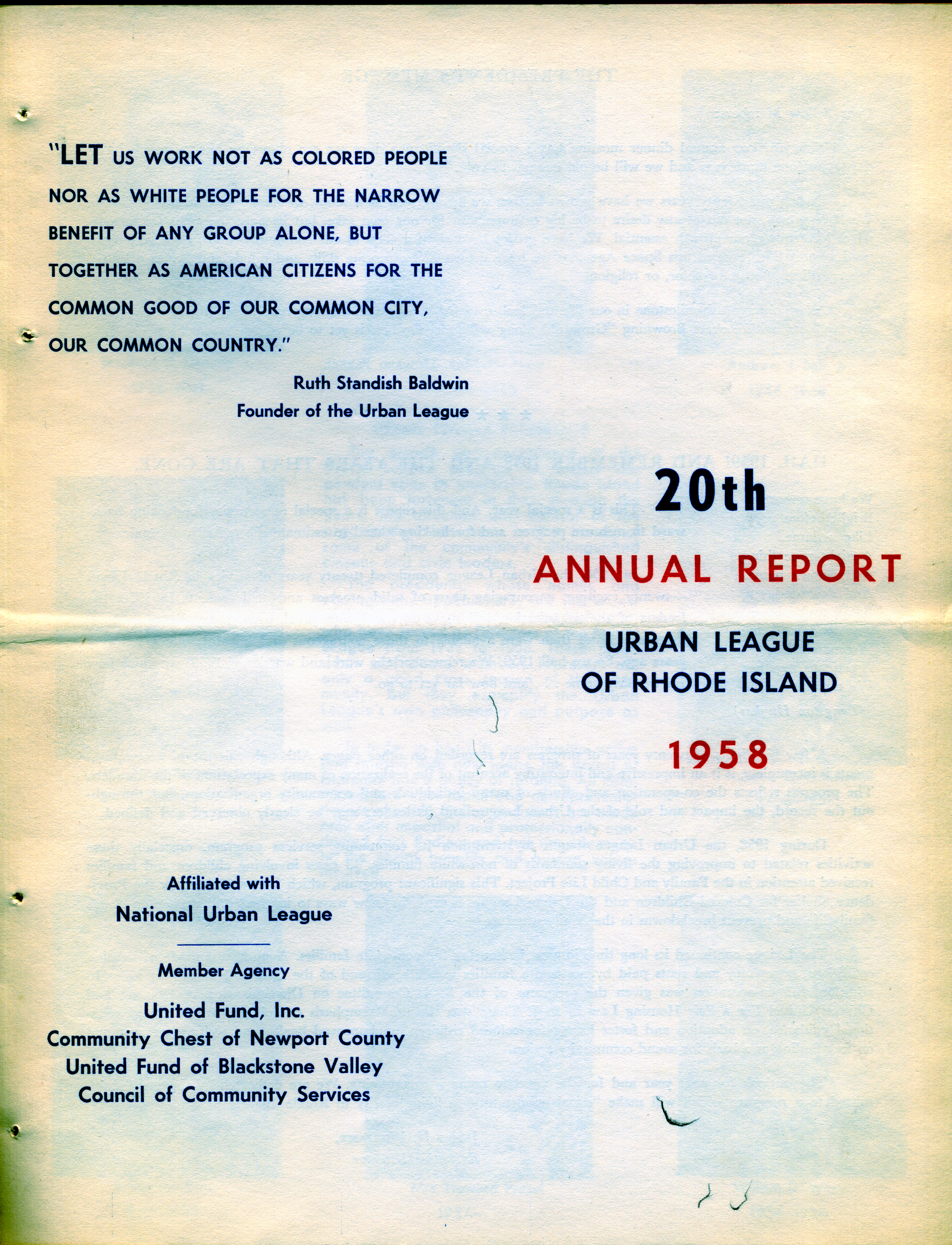

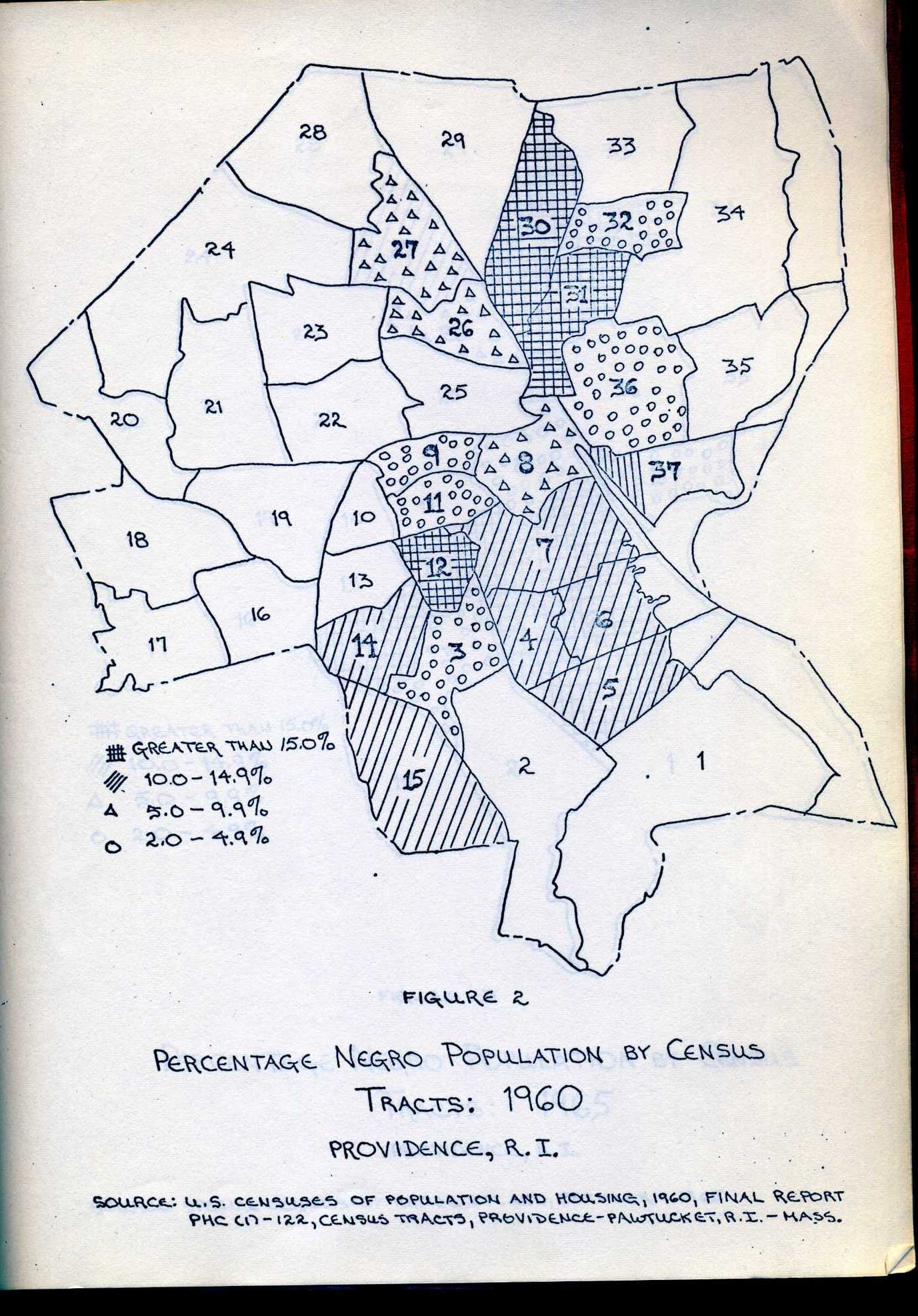

Using data from the 1960 Census, this map represents the clustering of Providence’s black population into particular neighborhoods. Most black residents of Providence were excluded from the city’s outer neighborhoods, following the national trend of black families living in inner cities. In 1960, the highest concentrations of black residents were in what are today known as Mount Hope, Upper South Providence, the former neighborhood of Lippitt Hill, and parts of the West End, Elmwood, and Downtown areas. It is unclear, however, whether Providence's sizable Cape Verdean population is included in this demographic report.

Courtesy of the Providence Public Library, Rhode Island Collection

This photograph of a young girl with her doll on South Main St., Providence illustrates the pervading feeling of melancholy that the civil rights movement could not adequately provide for Rhode Island's marginalized black population. South Main St. would soon be gentrified and redeveloped as part of the city's plan, pushing the black residents out of the College Hill area.

Photograph by Charlotte Estey, c. 1950

Courtesy of the Rhode Island Historical Society

Part of a longer conversation series, “Living” features a diverse range of black panelists from Rhode Island describing their experiences as black men in a segregated city. The following is a transcript of their discussion, which was originally held at the WJAR 10 television station.

Read the full transcript here.

Courtesy of the Providence Public Library, Rhode Island Collection

The front page of the August 28, 1963 Evening Bulletin prominently features photographs of Rhode Islanders on their way to D.C. for the March on Washington. More than 350 Rhode Islanders participated in this large scale “March for Jobs and Freedom,” reflecting some activists’ commitment to desegregation at both local and national levels.

Read more Civil Rights-era articles from the Providence Journal and Evening Bulletin here.

Courtesy of the Providence Public Library

In 1964, with the help of a Ford Foundation grant, Brown University established a cooperative exchange program with Tougaloo College, a Historically Black College in Jackson, Mississippi. The exchange program encouraged Brown and Tougaloo students and faculty to study at one another’s universities, allowing them to better understand the regional, financial, and racial differences between—and establish stronger ties across—these radically distinct institutions. As part of this exchange, Brown professor Ned Greene is seen here leading a chemistry class of Tougaloo students.

Courtesy of the Tougaloo College Archives and Freedom Now!

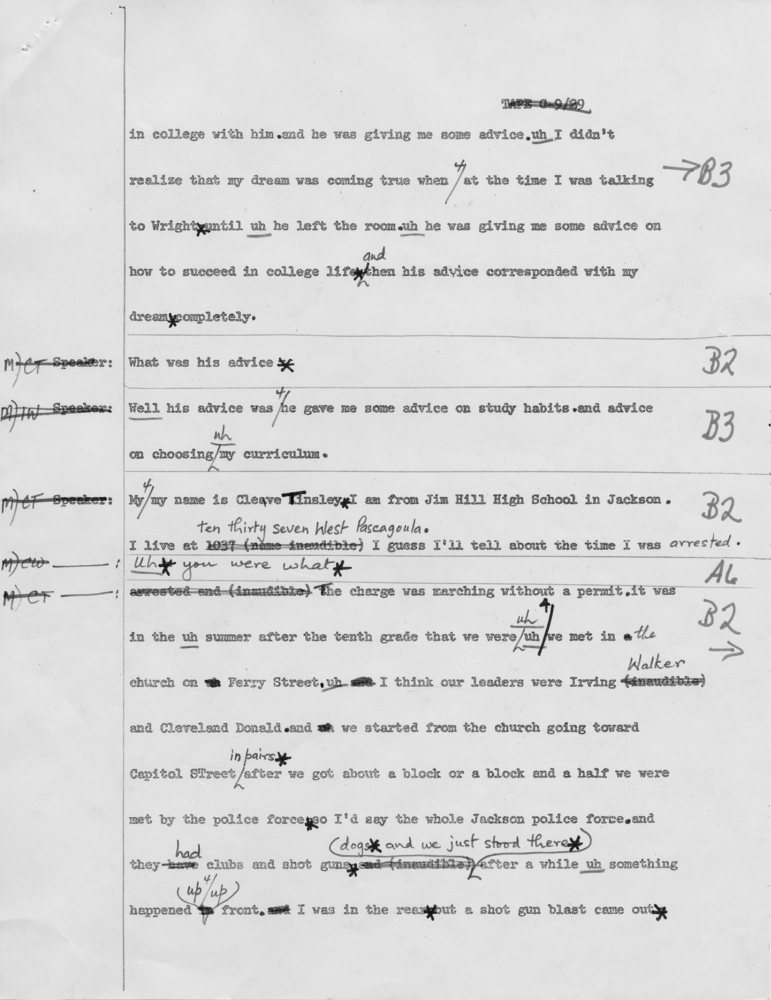

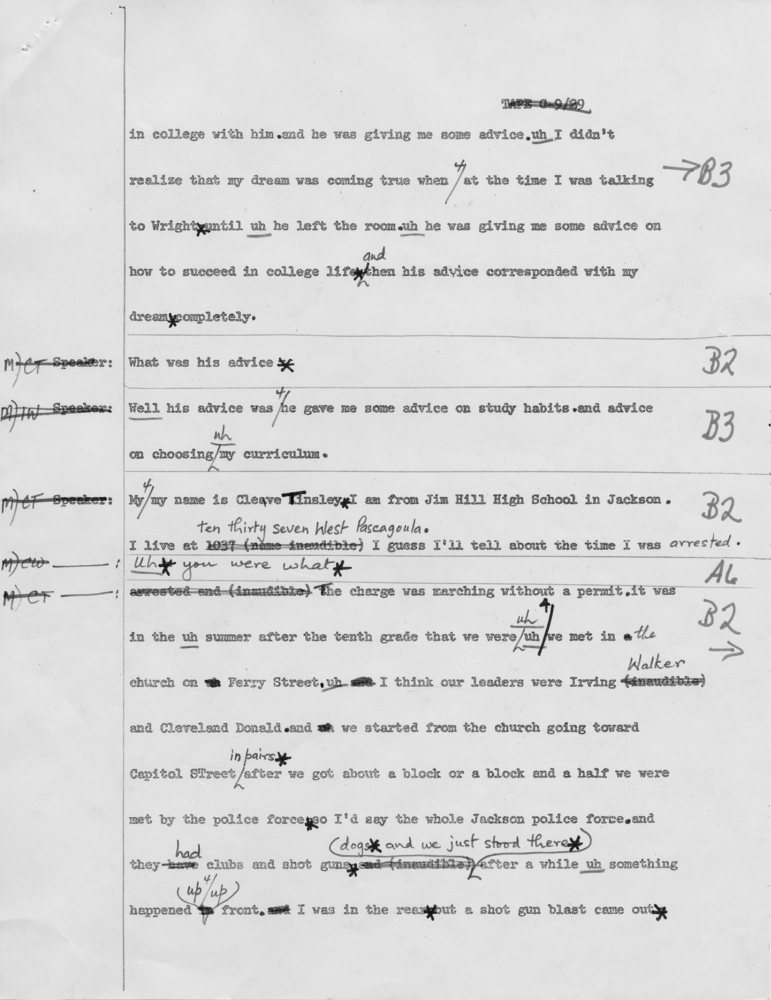

This is an edited transcript of a vocal recording used for analysis in the Brown-Tougaloo Language Project (BTLP). Here, a Tougaloo pre-freshman described being taken to jail for peacefully protesting. The excerpt illustrates both the activism of Tougaloo students and the work being done by the BTLP.

Courtesy of the Tougaloo College Archives and Freedom Now!

This celebratory photograph highlights achievements of black Rhode Islanders, here observing their successful fundraising drive. The multigenerational event was importantly sited at the Congdon Street Baptist Church, which opened in 1820 as the African Union Meeting and Schoolhouse.

Courtesy of the Rhode Island Historical Society

On December 5, 1968, black female students at Pembroke college initiated a walkout, rallying black students at Brown to march out of the university and to the Congdon Street Baptist Church, where they successfully negotiated with the institution for three days on matters of race. The “Walkout of 1968” was triggered by the lack of an existing University-wide commitment to address the improvement of black student representation within Brown’s student body. Soon after, Brown established the framework by which it would measure improvements on race-related issues.

Courtesy of the Rhode Island Historical Society