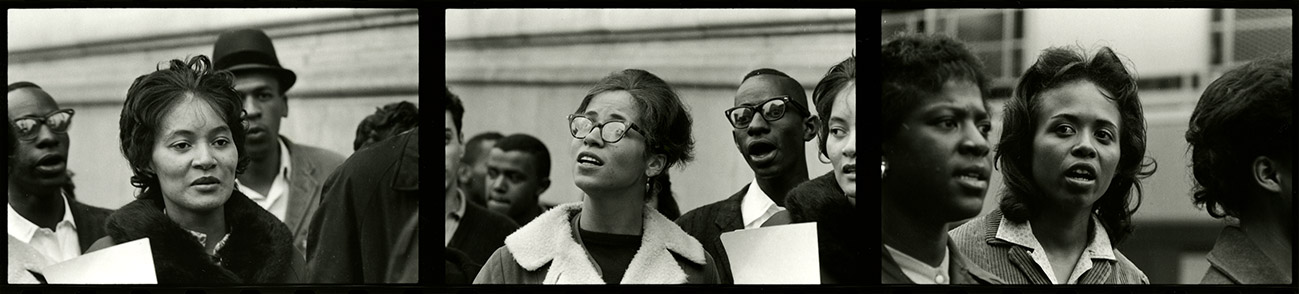

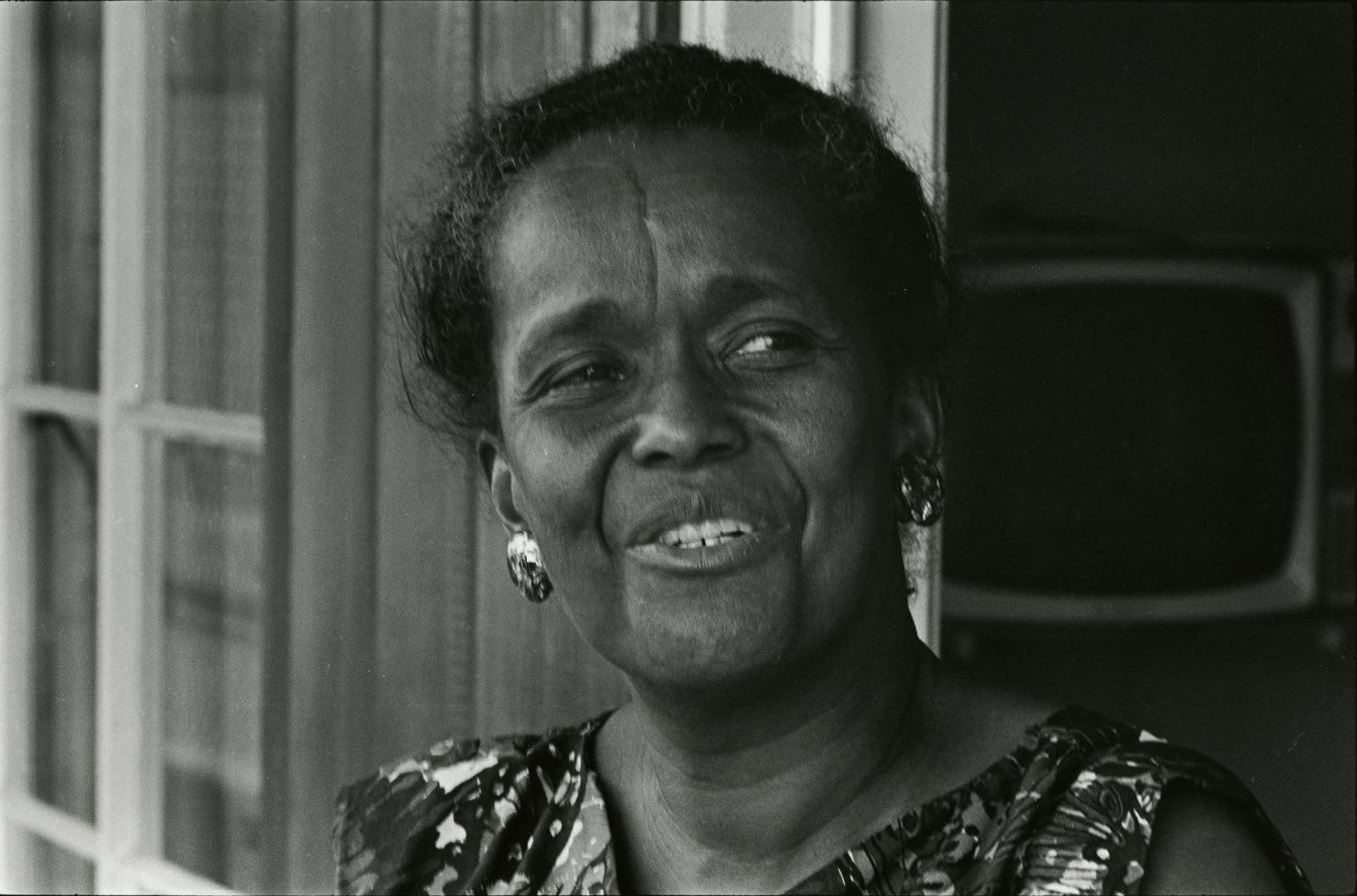

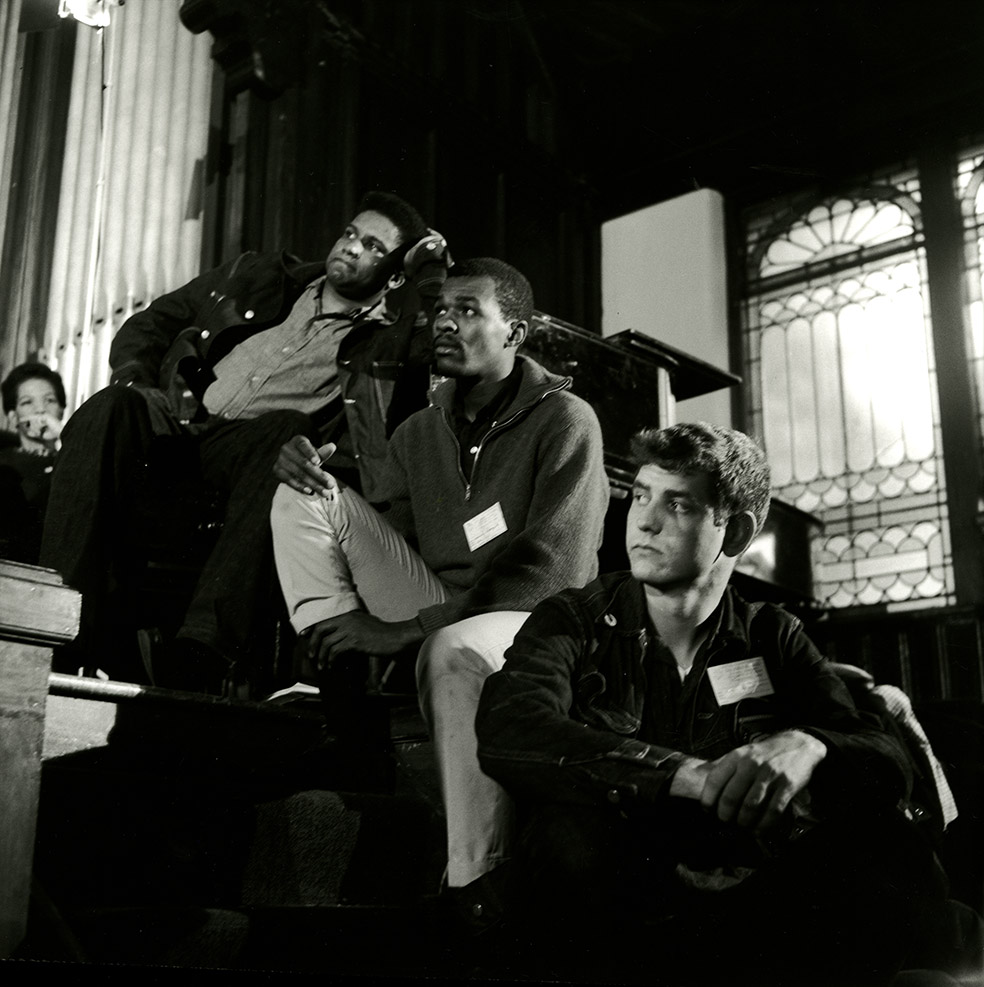

In 1960, when Lyon was still an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, a growing student protest movement was forming in Nashville, Tennessee. Civil rights activist Ella Baker saw powerful political potential in these youth demonstrations and helped organize the first large-scale students’ meeting at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina in April l960. The three hundred students who came, including Chuck McDew, felt that nonviolent tactics would not work as well as direct action. As McDew said, “You cannot make a moral appeal in the midst of an amoral society.” Many student activists agreed with him, and together they decided to form their own organization. Nonetheless, others still believed in the importance of nonviolent principles, particularly in the fight for voter registration. Through this dual project, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was officially formed.

Lyon arrived in Cairo, Illinois at the same time that the town was divided, once again, over the segregation of a public establishment. Here, a swimming pool marked for “members only” is transformed as the site of a protest as black residents, towels and bathing suits in hand, demonstrated for entrance.

The demonstrators at the community pool in Cairo exercised the nonviolent form of protest which SNCC members like John Lewis strongly advocated. Several young black men led the line outside the pool, marching calmly even as tensions in the surrounding white crowds reacted with increasing anger and provocation.

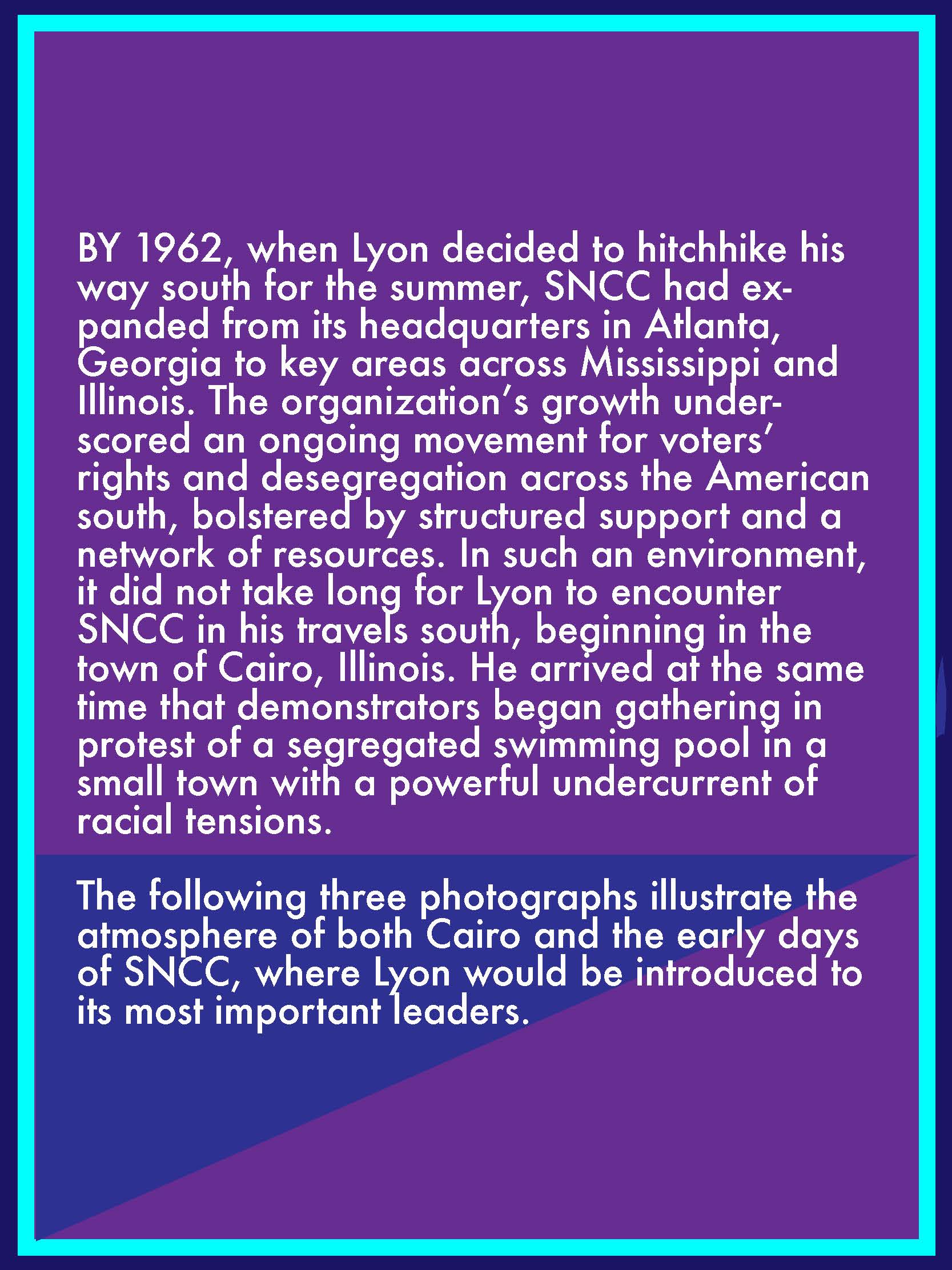

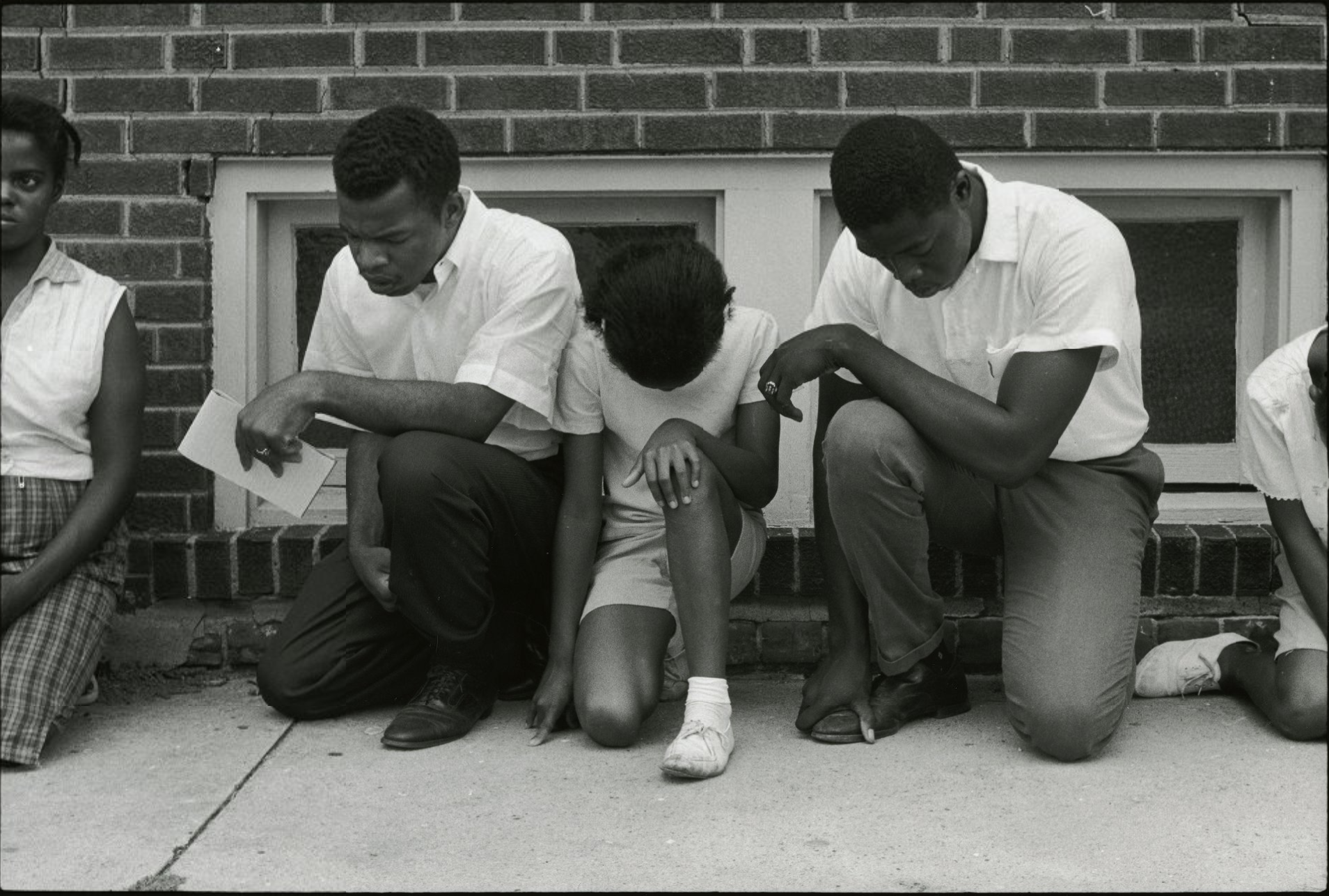

Many of Lyon’s photographs of the civil rights movement would be used in political campaigns and donations for SNCC, raising the organization’s profile both domestically and abroad. This image, capturing John Lewis and fellow protestors praying during a demonstration in Cairo would become one of Lyon’s most recognized and circulated works during his time with SNCC.

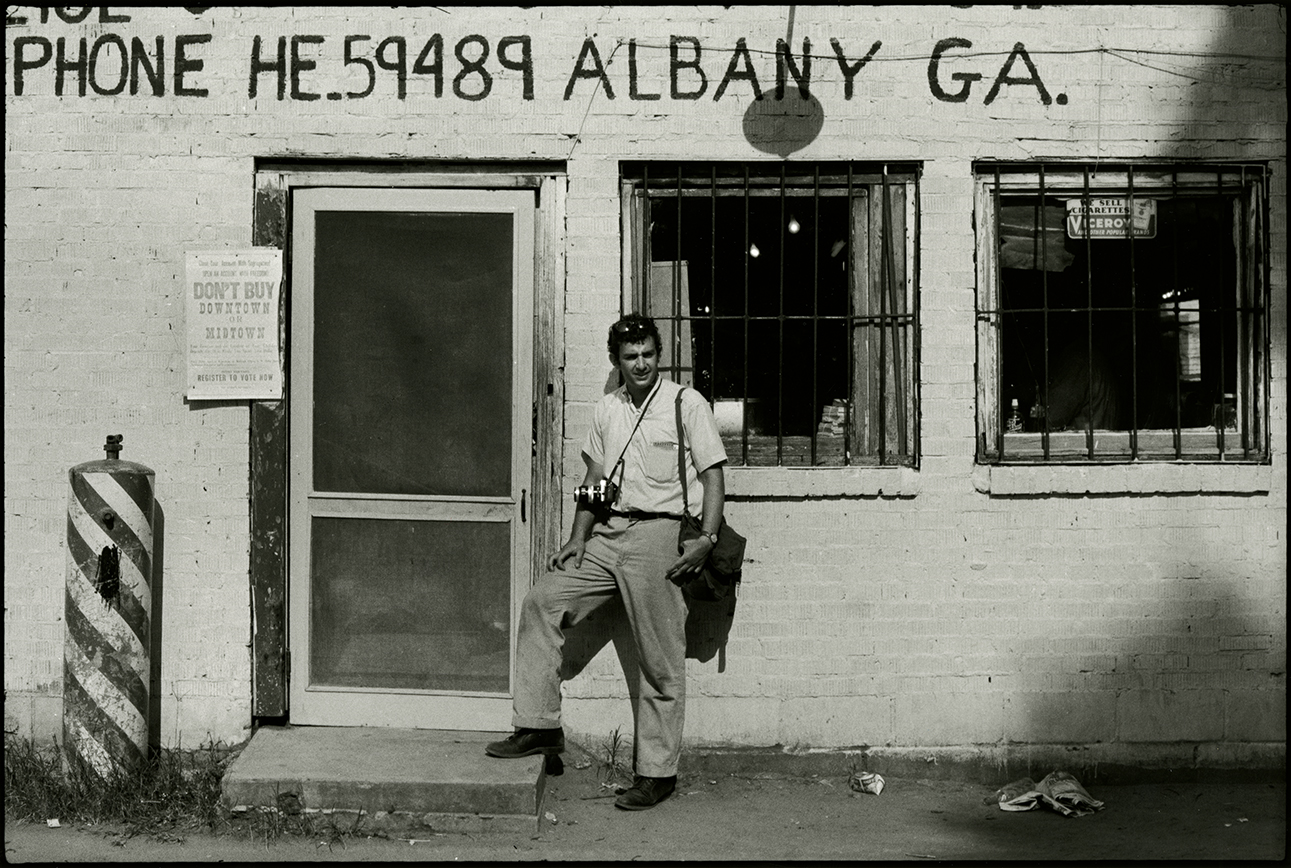

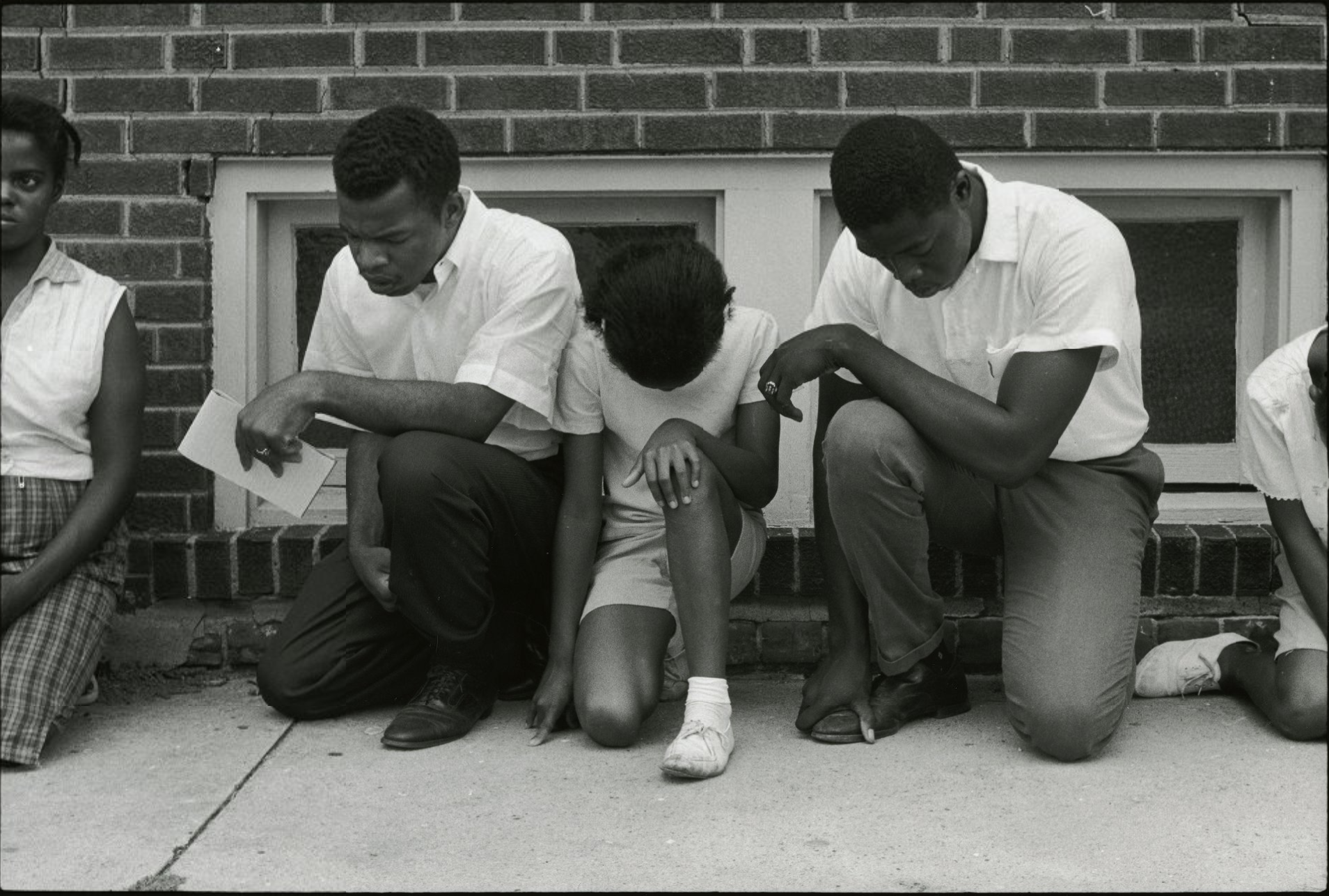

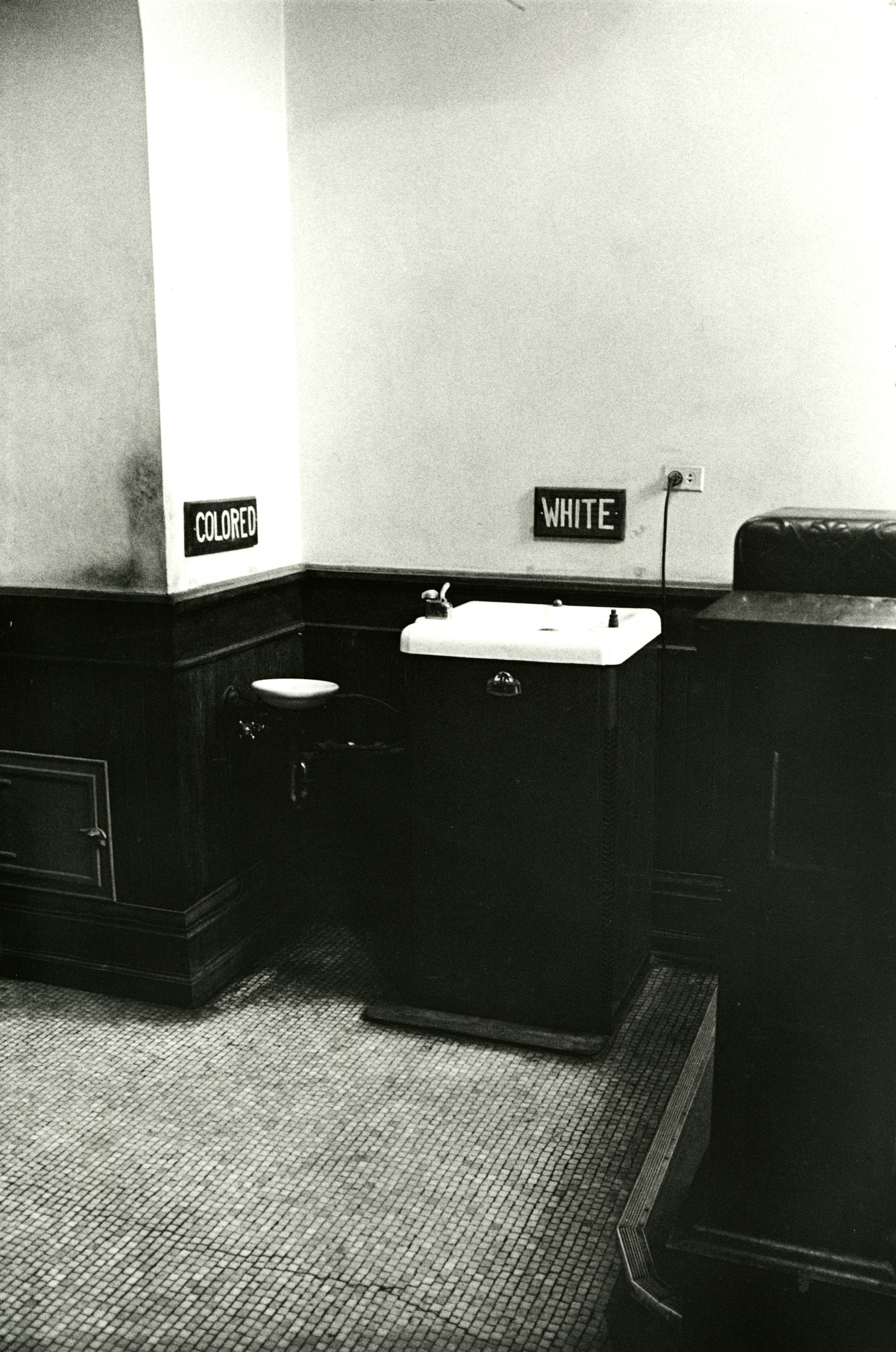

Shortly after his stop in Cairo, Illinois, Lyon travelled to Albany, Georgia. He reached the city in August 1962, where he first met SNCC executive secretary James Forman, who immediately sent him to document the movement. Lyon included photographs of existing structural discrimination, such as this segregated water fountain in the Albany courthouse. Forman was an early supporter of Lyon’s involvement with SNCC, recognizing the importance of keeping a visual archive of the movement—one that, as Lyon explained, would be “used to help create a public image for SNCC.”

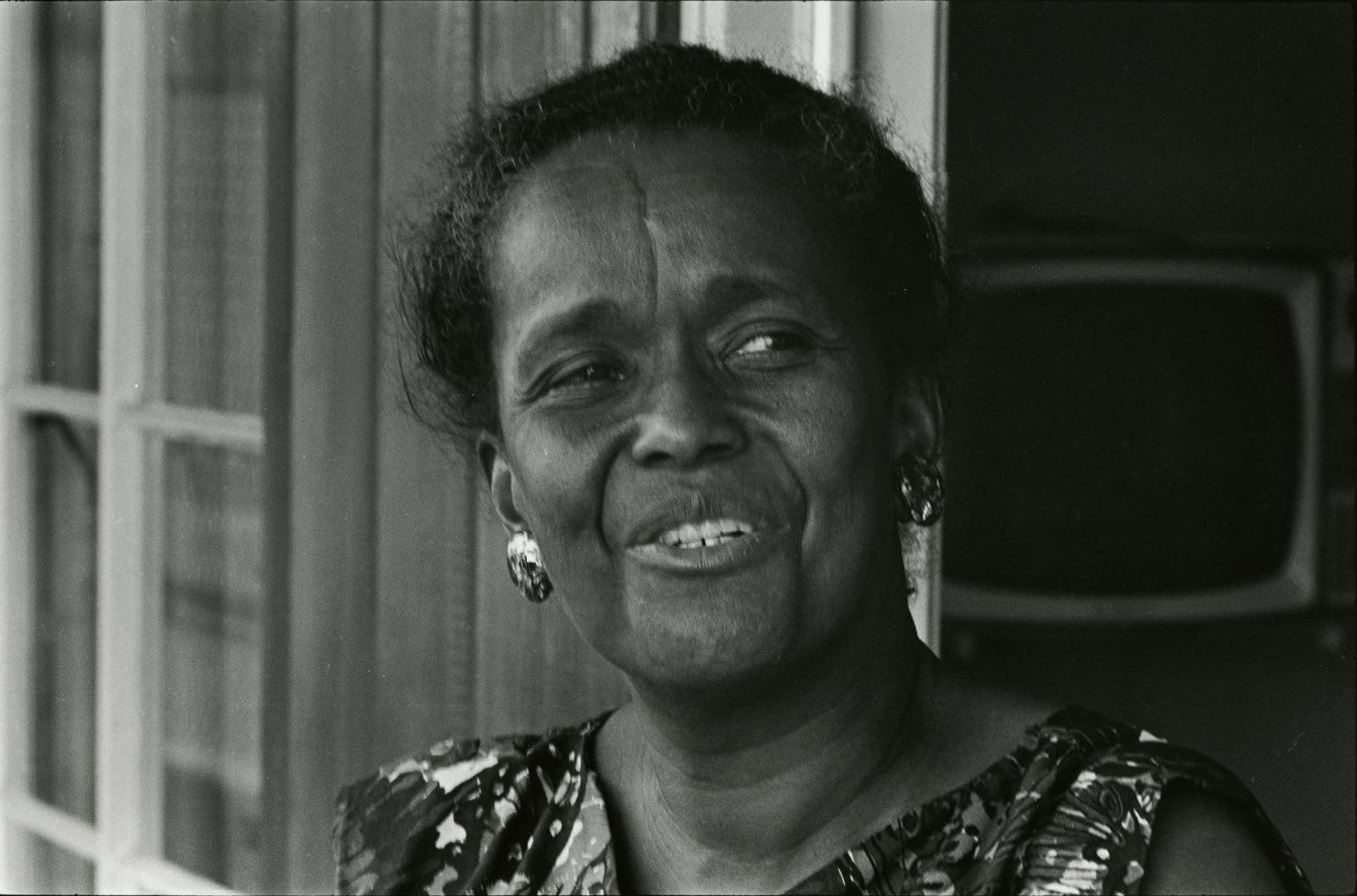

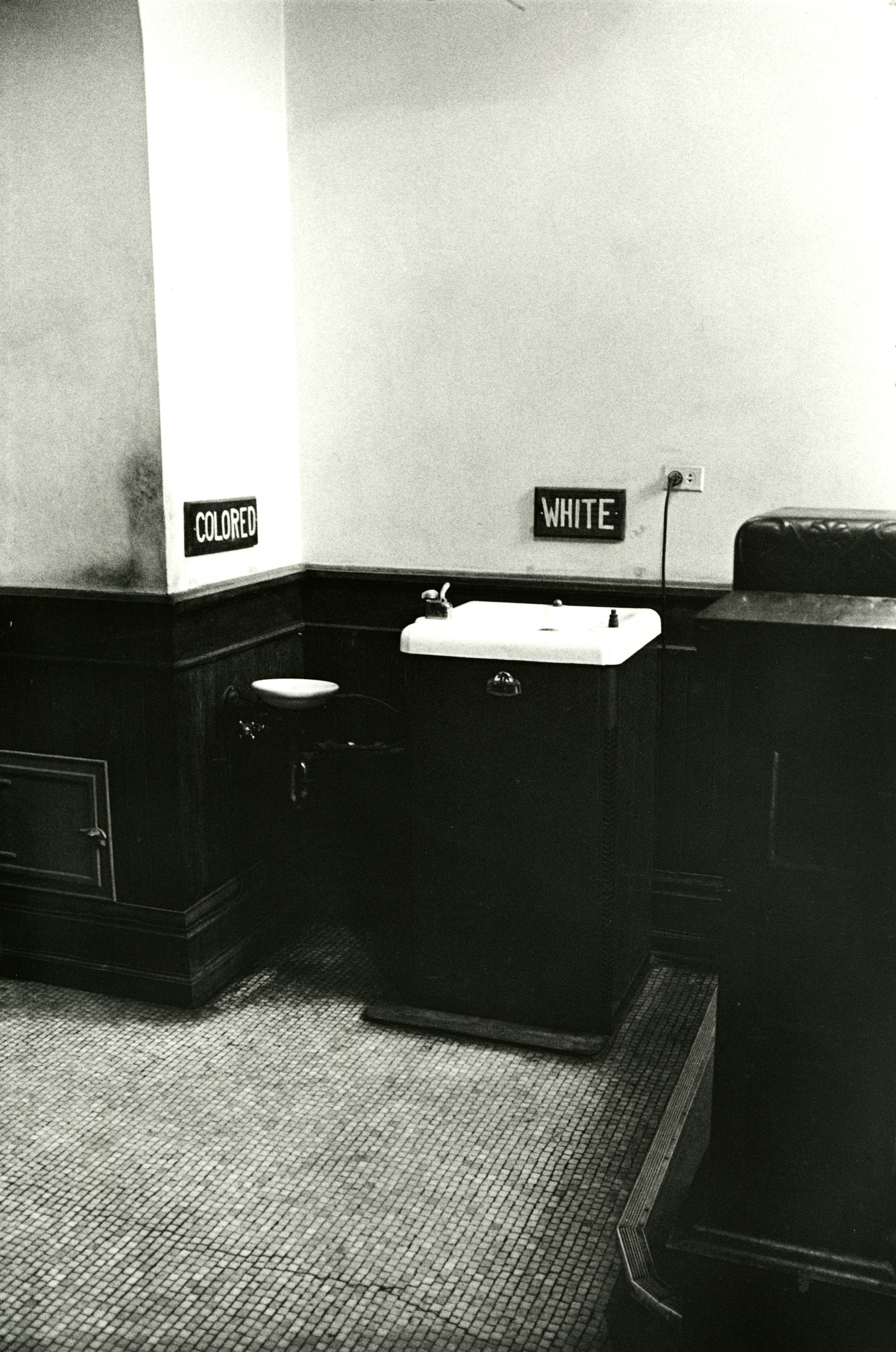

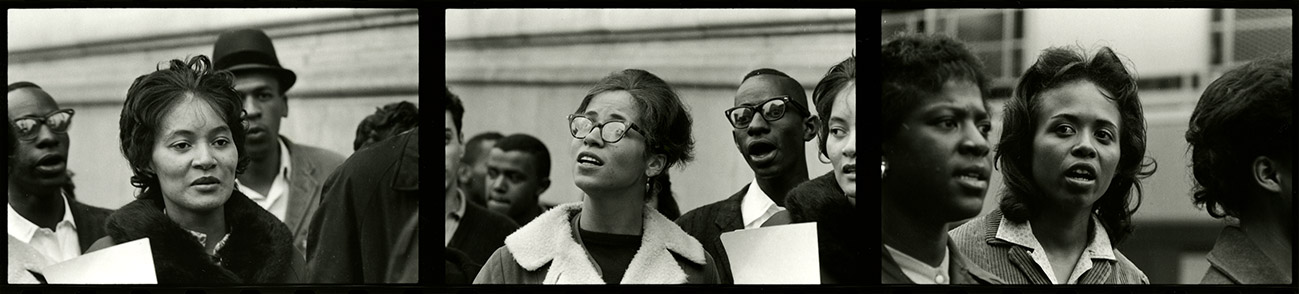

Lyon’s next documenting trip led him to Nashville, Tennessee in November 1962. The city would host the annual SNCC conference, where leaders from across the southern United States gathered, many of whom were women. Activists such as Joy Reagon, Peggy Dammond, and Dorie Ladner led a march through downtown Nashville after the conference, exemplifying the voice of the movement and the need for continuous action.

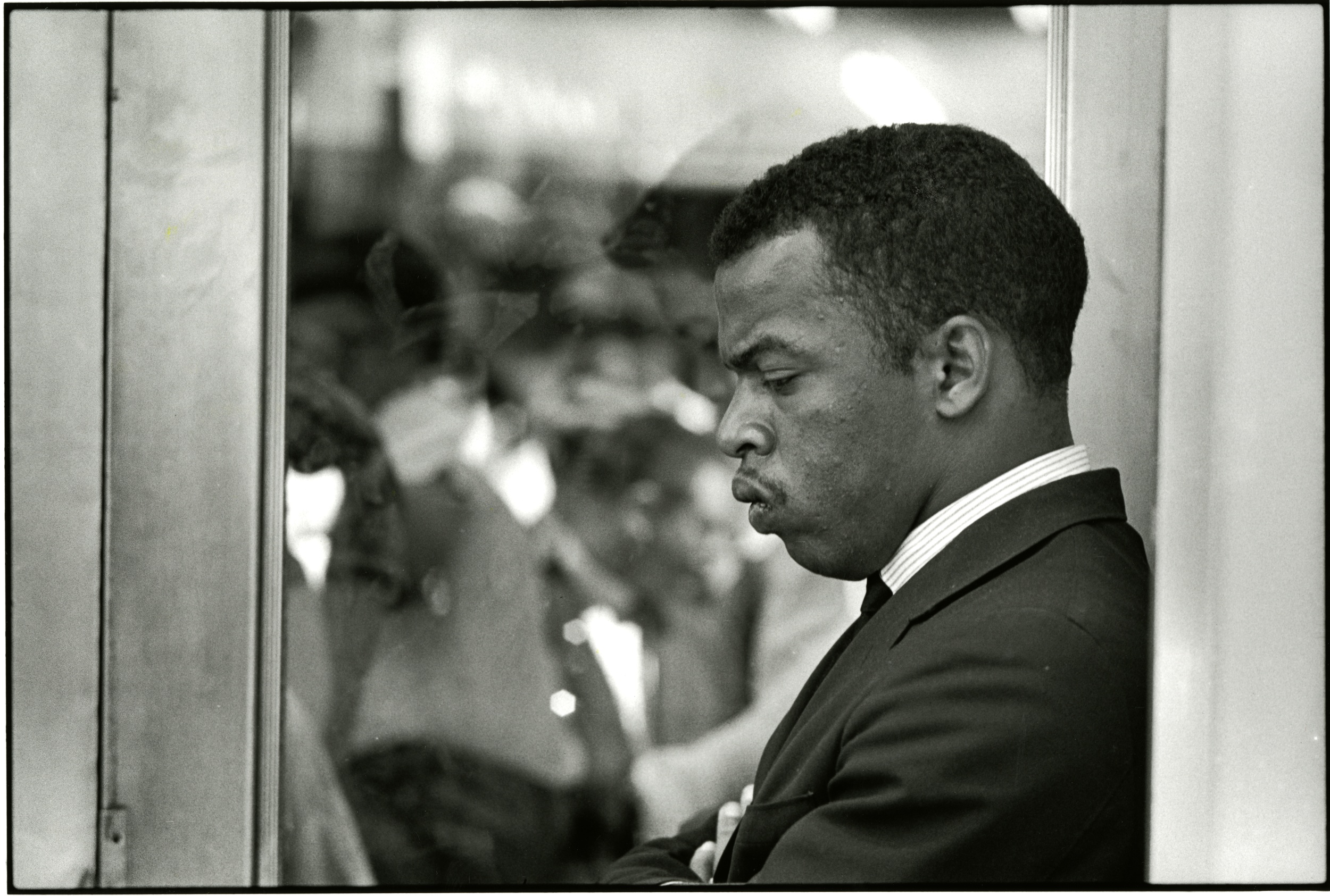

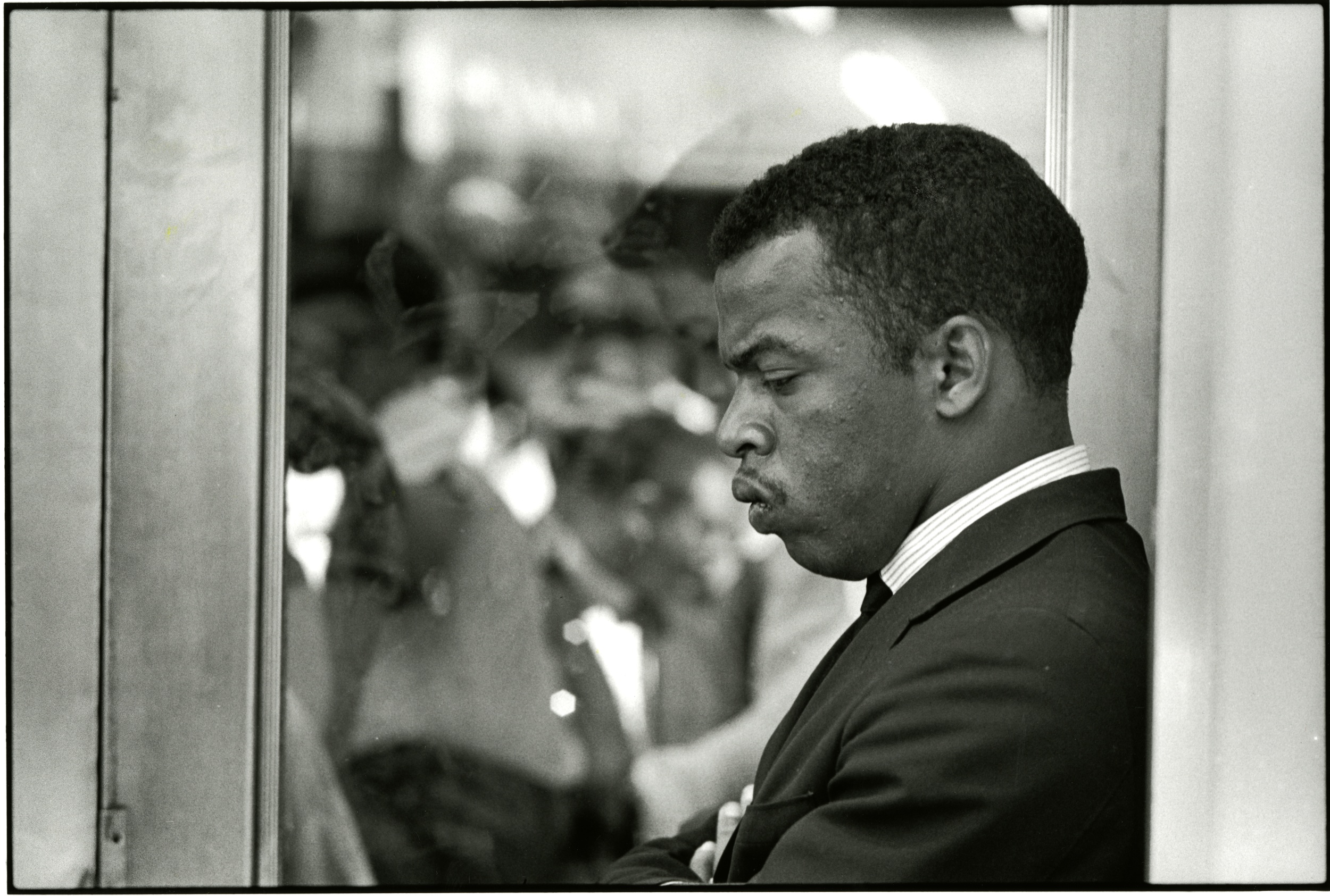

Along with others at SNCC, the young activist John Lewis would become a close friend to Lyon. Lewis was already well known at that time for being a rousing public speaker and a strong leader in the early protest movements. Lyon remembers hearing Lewis speak for the first time at a church in Cairo: “The speech, delivered in a heavy, rural Alabama accent, seemed to come up out of him, out of centuries of abuse, and explode from this unassuming young man. His voice was high pitched and trembling with emotion. John’s speech would have converted anyone, and it converted me.”

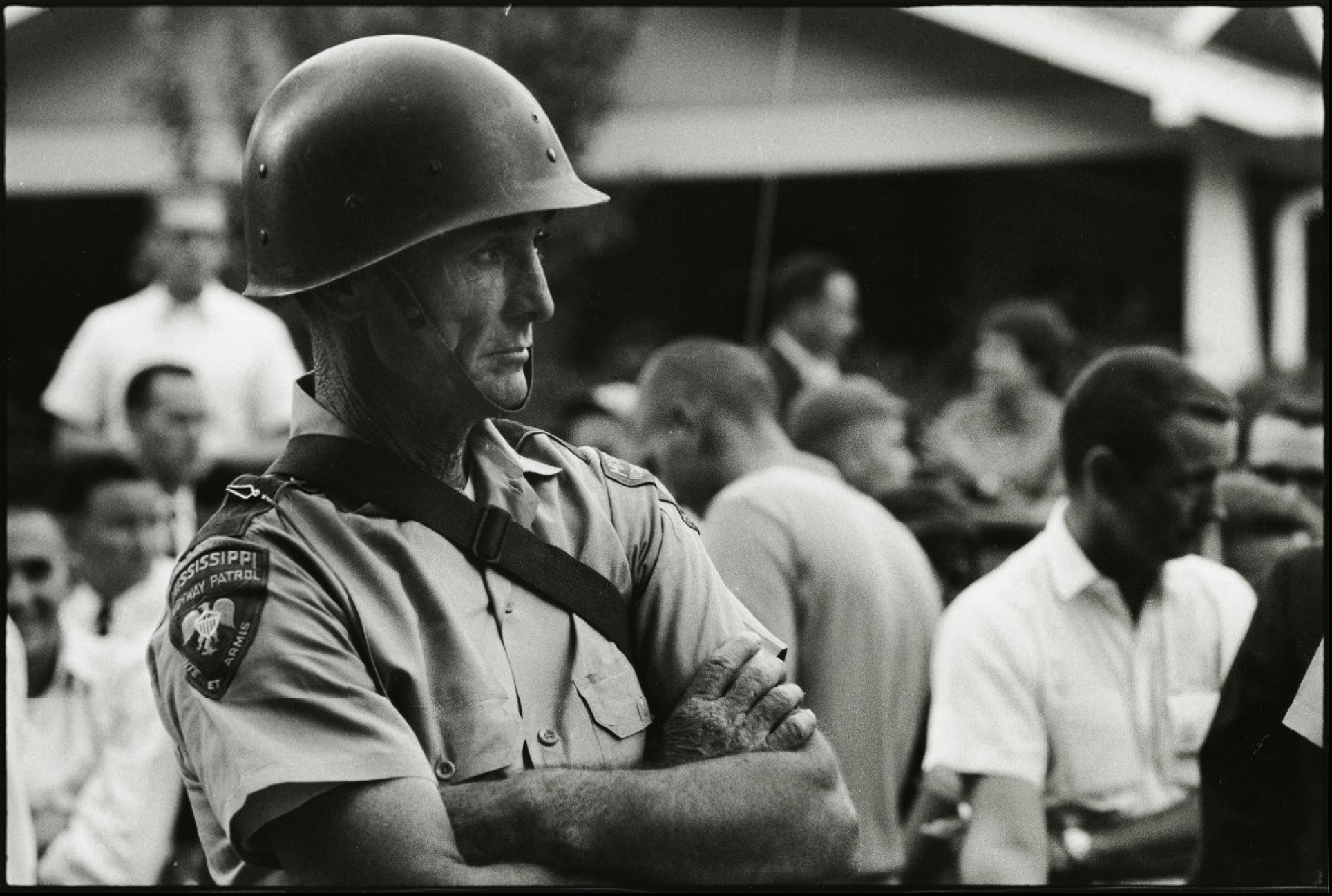

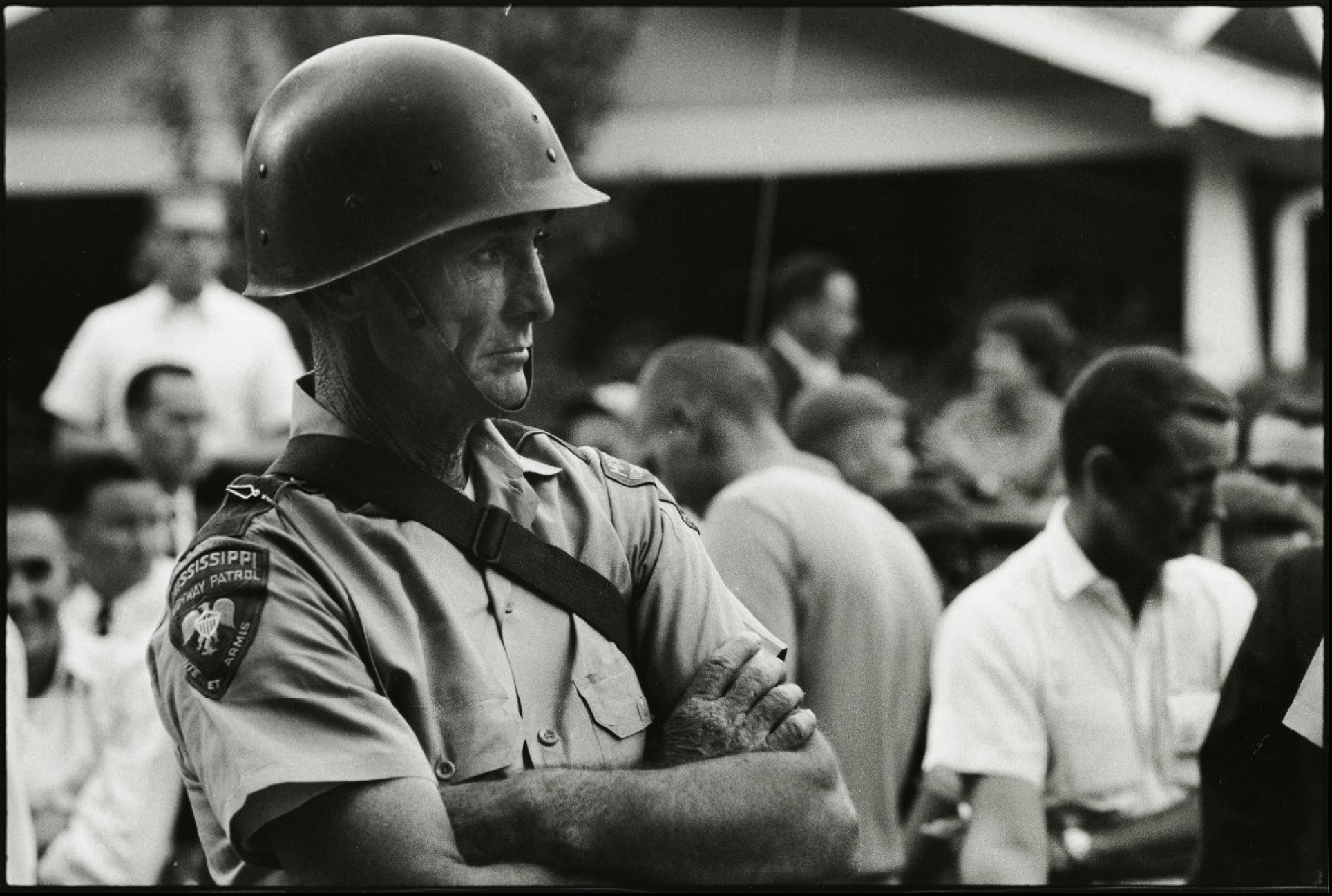

Lyon made frequent trips to Winona, Mississippi between 1962 and 1963. During one of his earlier visits, he took this picture of a police officer on the University of Mississippi campus. It was here that black college student James Meredith attempted to register for courses in the segregated school, inciting a violent backlash. The image Lyon took on campus was used in SNCC posters and fundraising flyers, accompanied with the question, “Is he protecting you?”

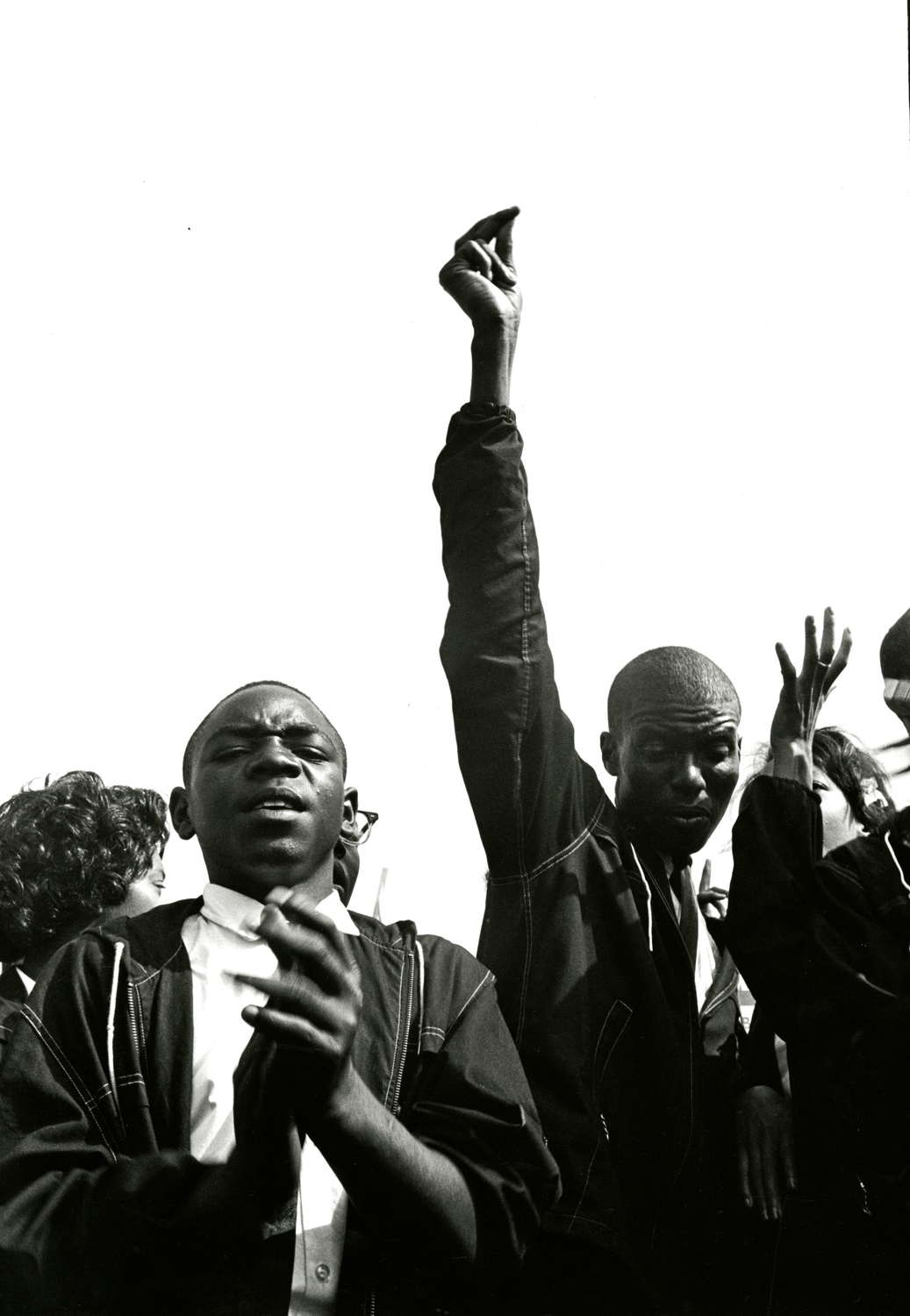

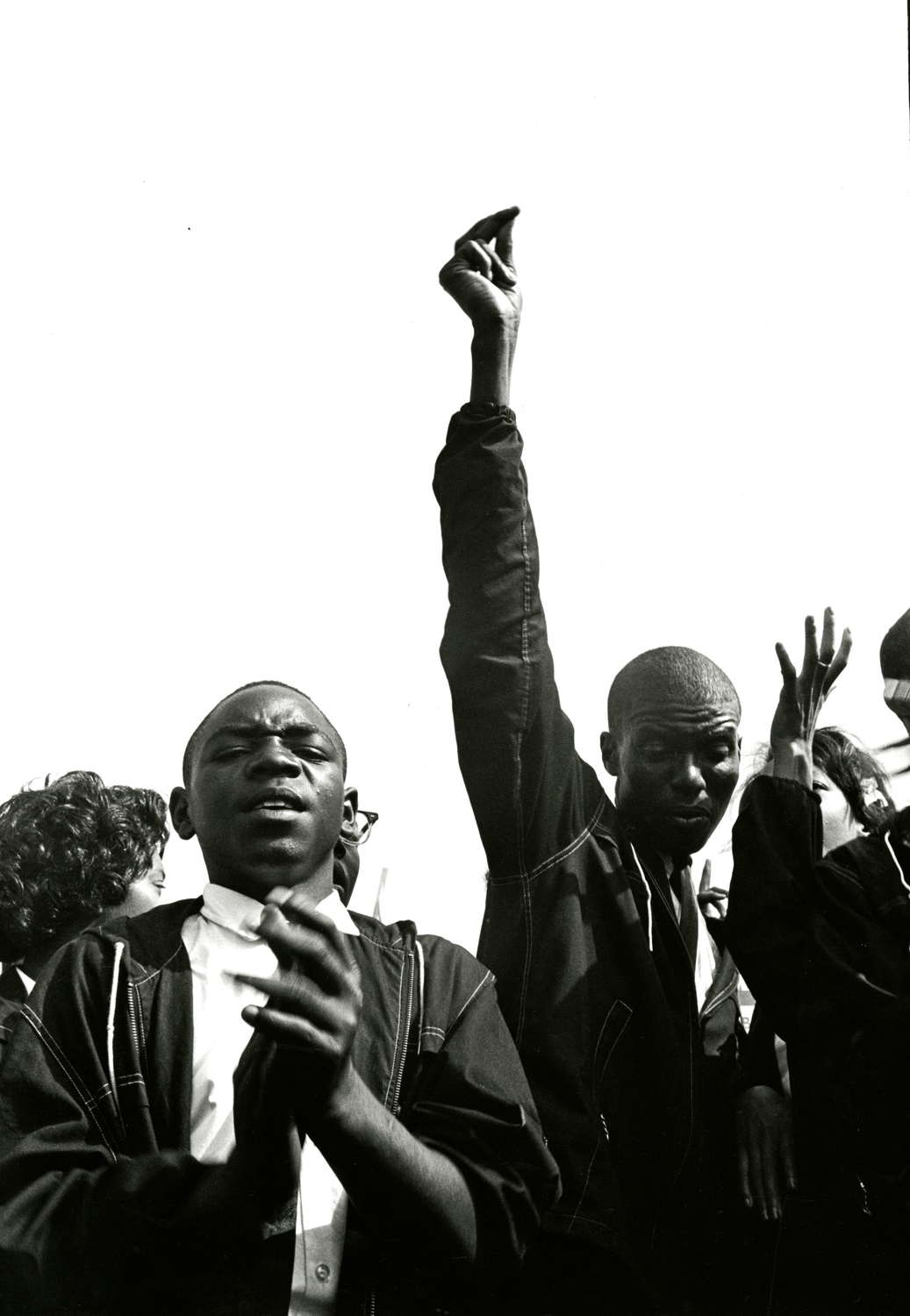

The rallying demonstration in Danville, Virginia drew a huge crowd over a period of days. Several key SNCC players attended the protests, including Bob Zellner, Bernice Reagon, Cordell Reagon, Dottie Miller, and Avon Rollins, pictured here.

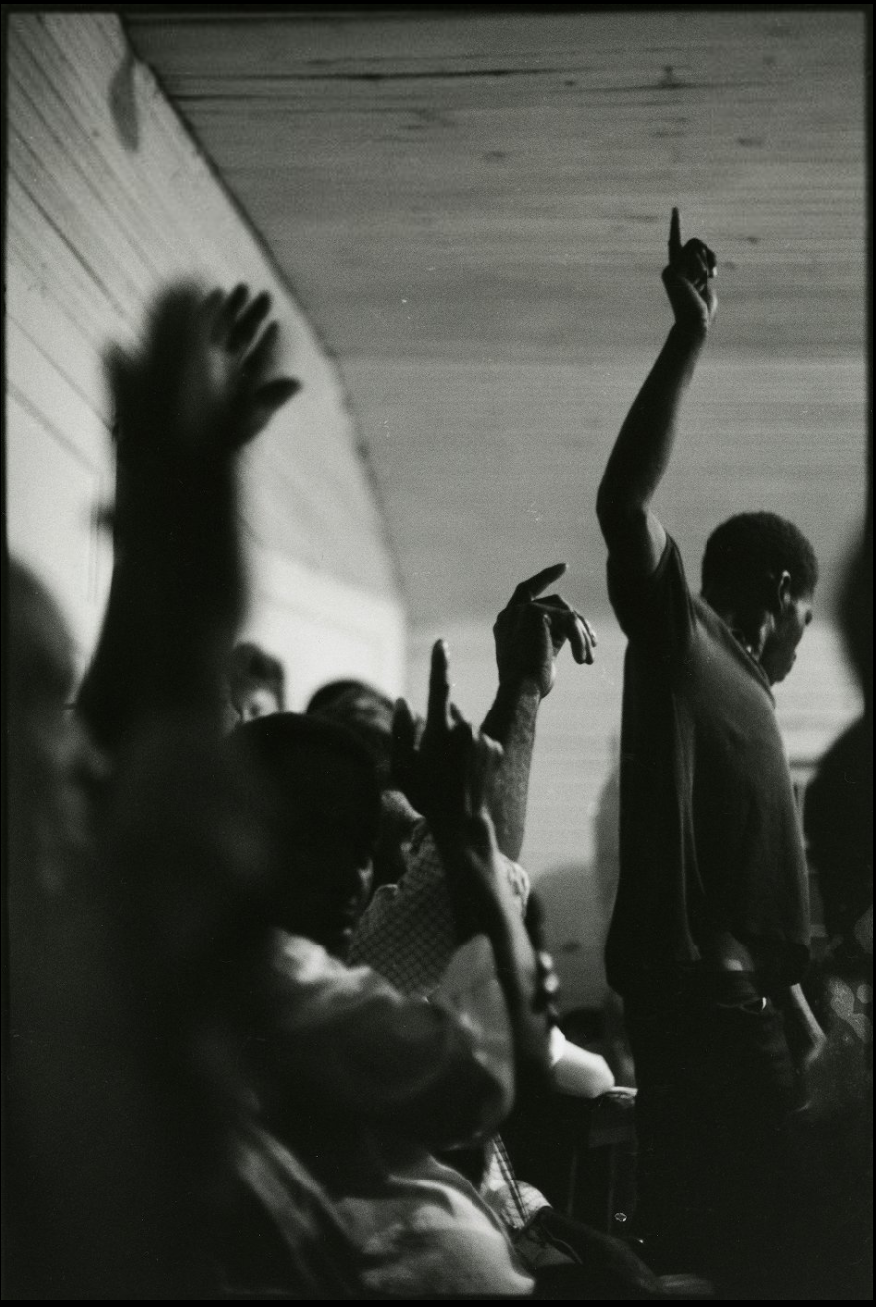

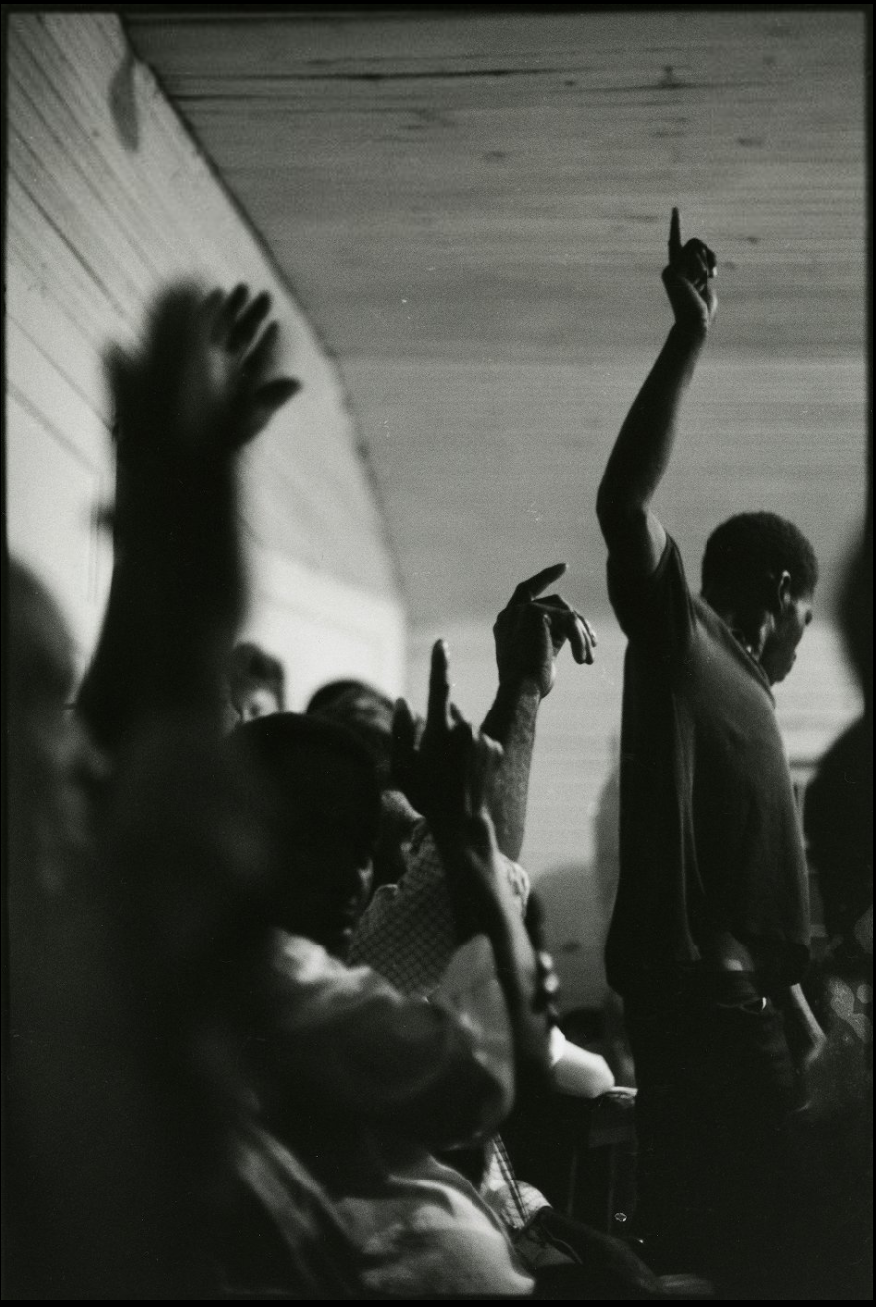

James Forman also attended the Danville protests, giving a moving and powerful speech to rally support and continue the momentum of a demonstration that had endured intense, and often brutal, community and police retaliation. This image captures the vitality of the meeting’s call to action only moments before the police arrived with tanks and full outfits to break up the demonstration in an unprecedented show of force against a peaceful rally.

In the summer of 1963, the March on Washington brought SNCC to the center of national attention. It was momentous moment for civil rights across the country, but many SNCC members felt disappointed by the political performance and staged rehearsal of the march. For many at SNCC, the organization’s local work on the ground felt more attuned to the goals of the movement than that of the message in Washington.

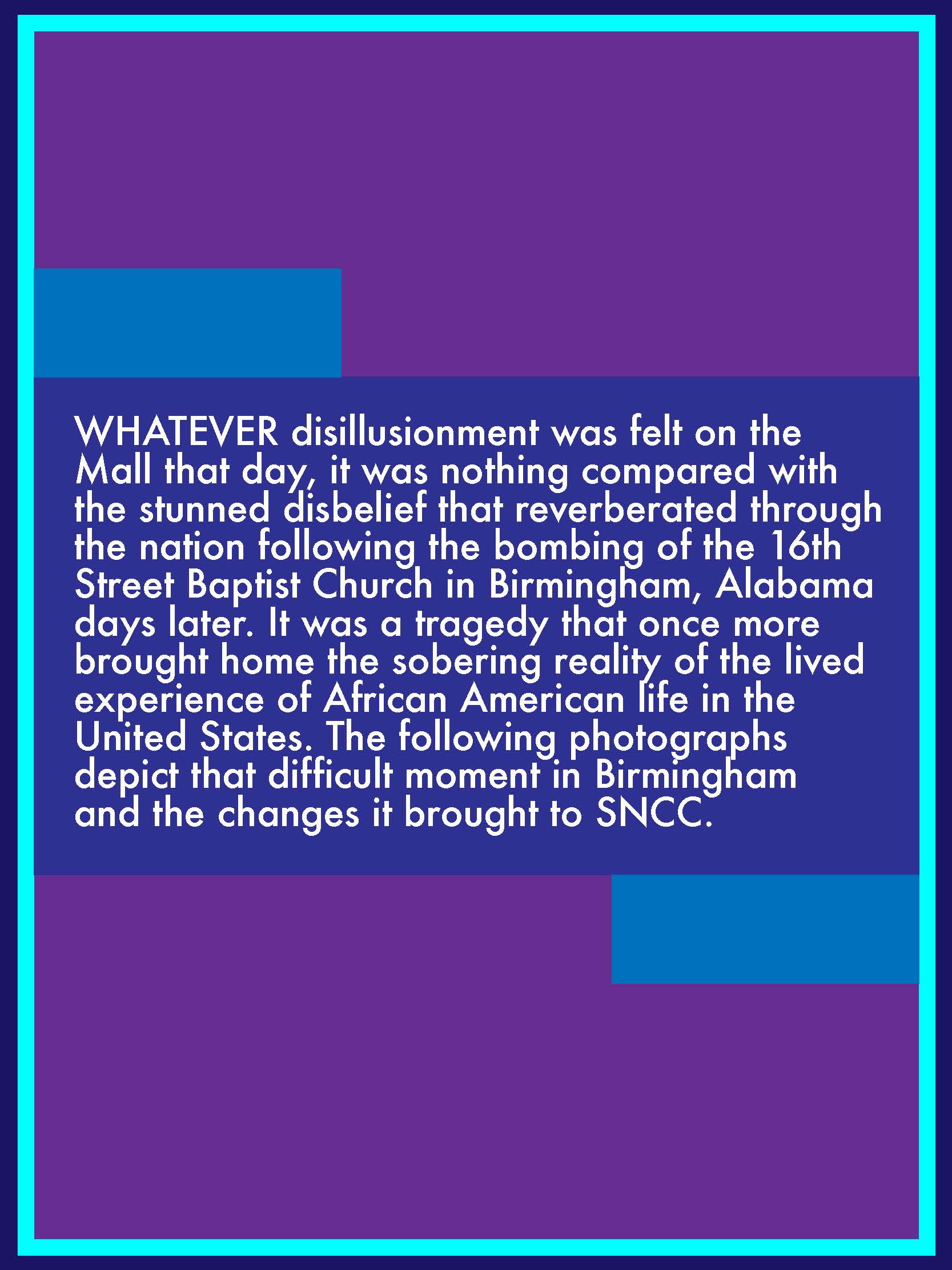

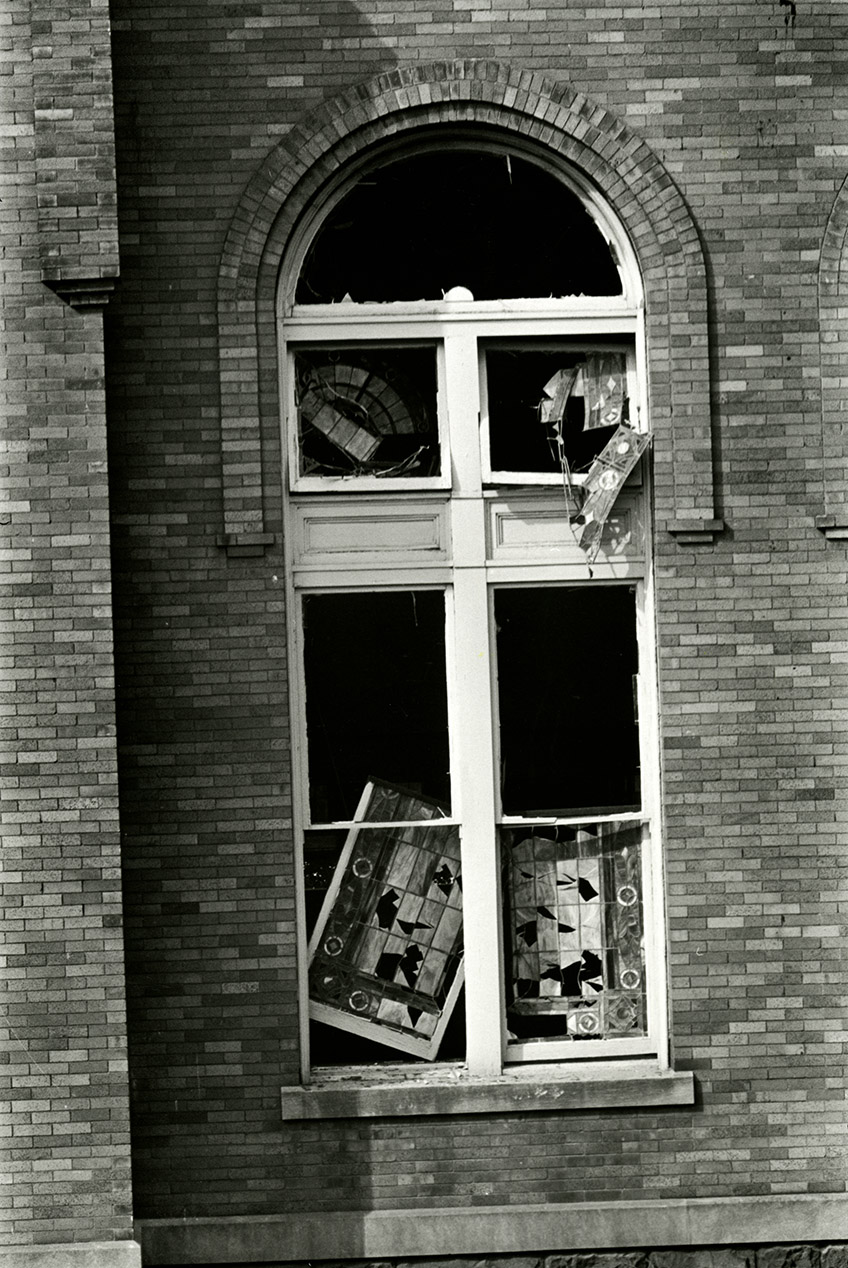

On Sunday, September 12, 1963 at 10:22AM, dynamite exploded through the floors of the 16th Street Baptist Church basement, killing four young girls and injuring dozens more. The bomb, planted by four members of the Ku Klux Klan, severely damaged the church, destroying all but one of the building’s stained glass windows.

The funeral march for the four girls killed in the bombing took place over the course of a few days following the attack. Thousands of mourners gathered along the funeral path to pay their respects and shoulder together the weight of an unbearable injustice.

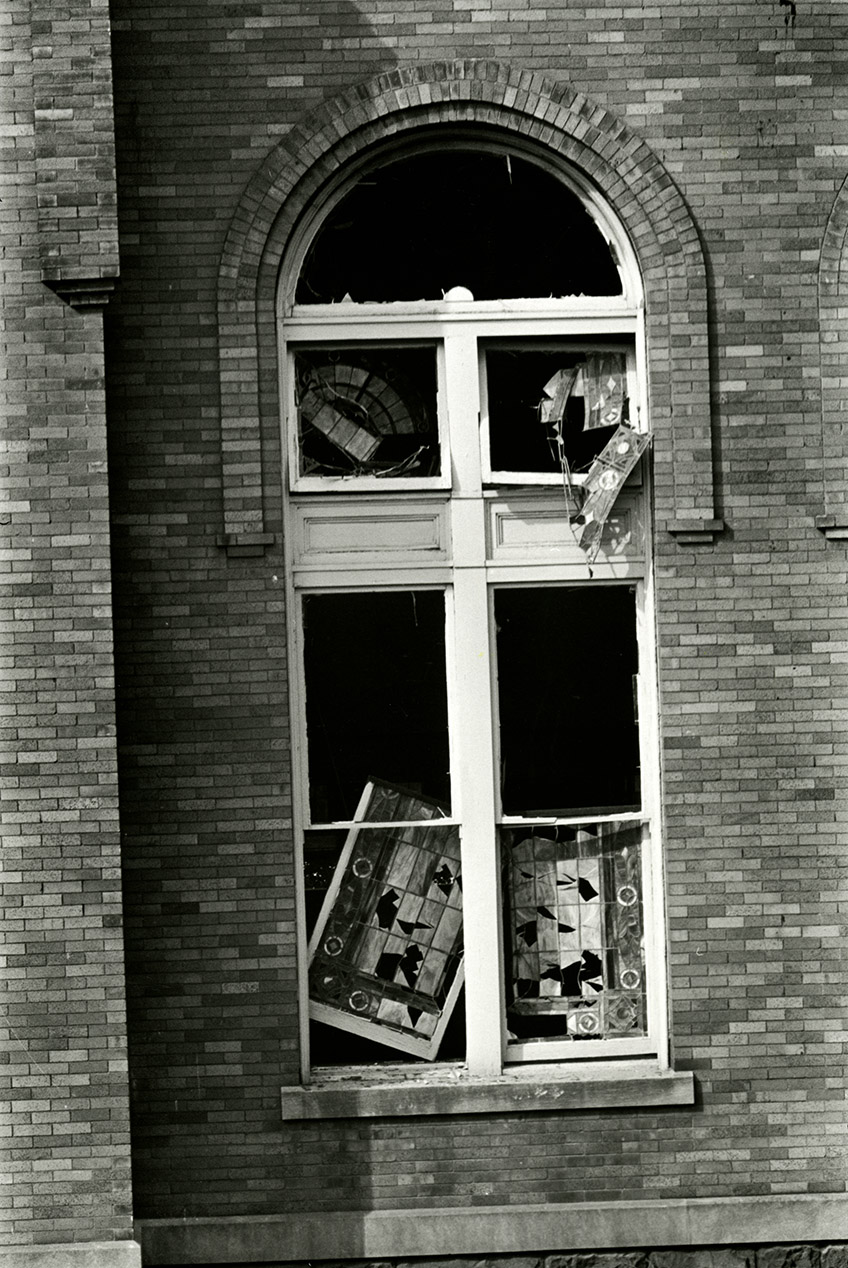

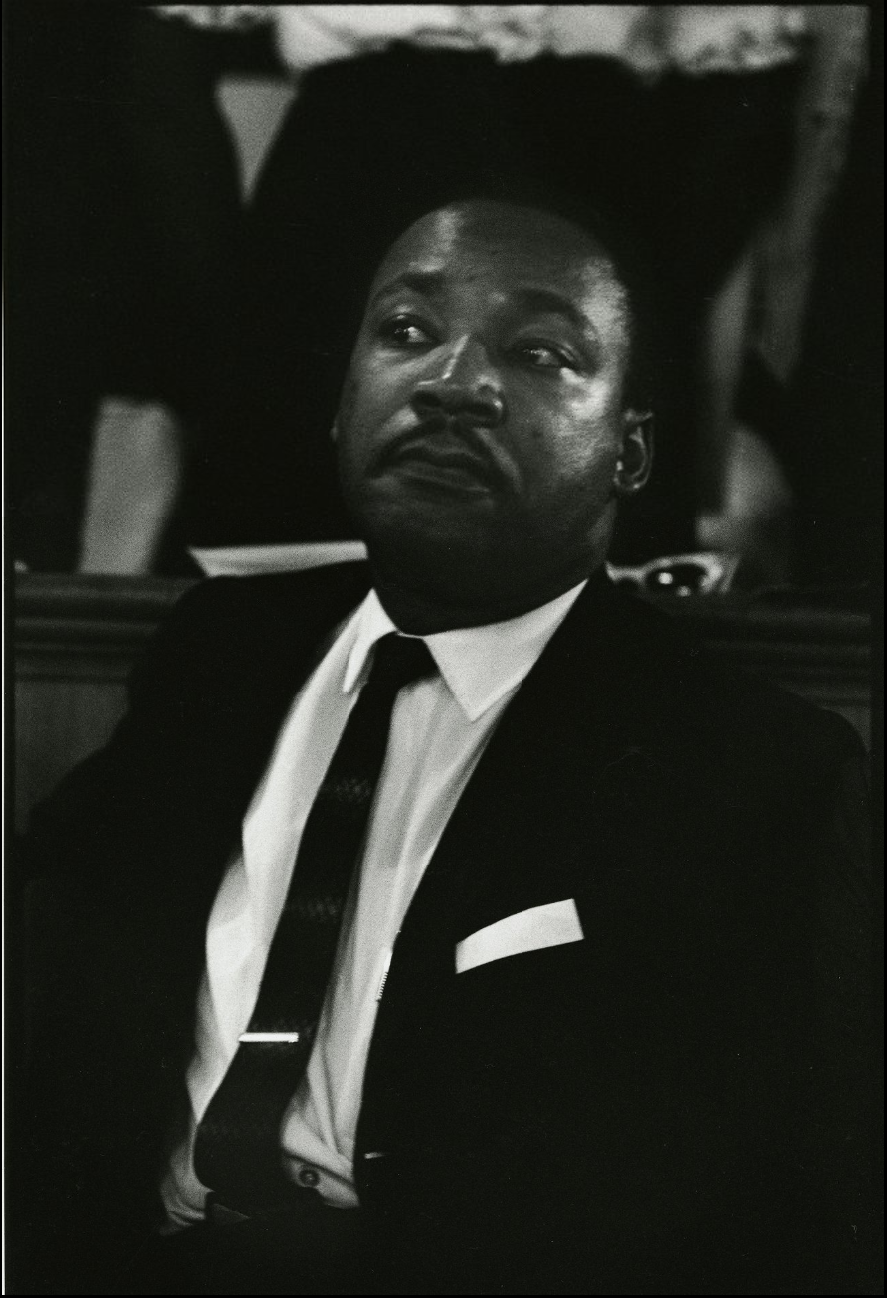

Over 3,000 mourners attended the public funeral for three of the four girls killed in the bombing. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., shown here quietly awaiting his turn to speak, gave the funeral address. His powerful words echoed the sentiments of millions listening near and far to the consequences of American racial injustice.

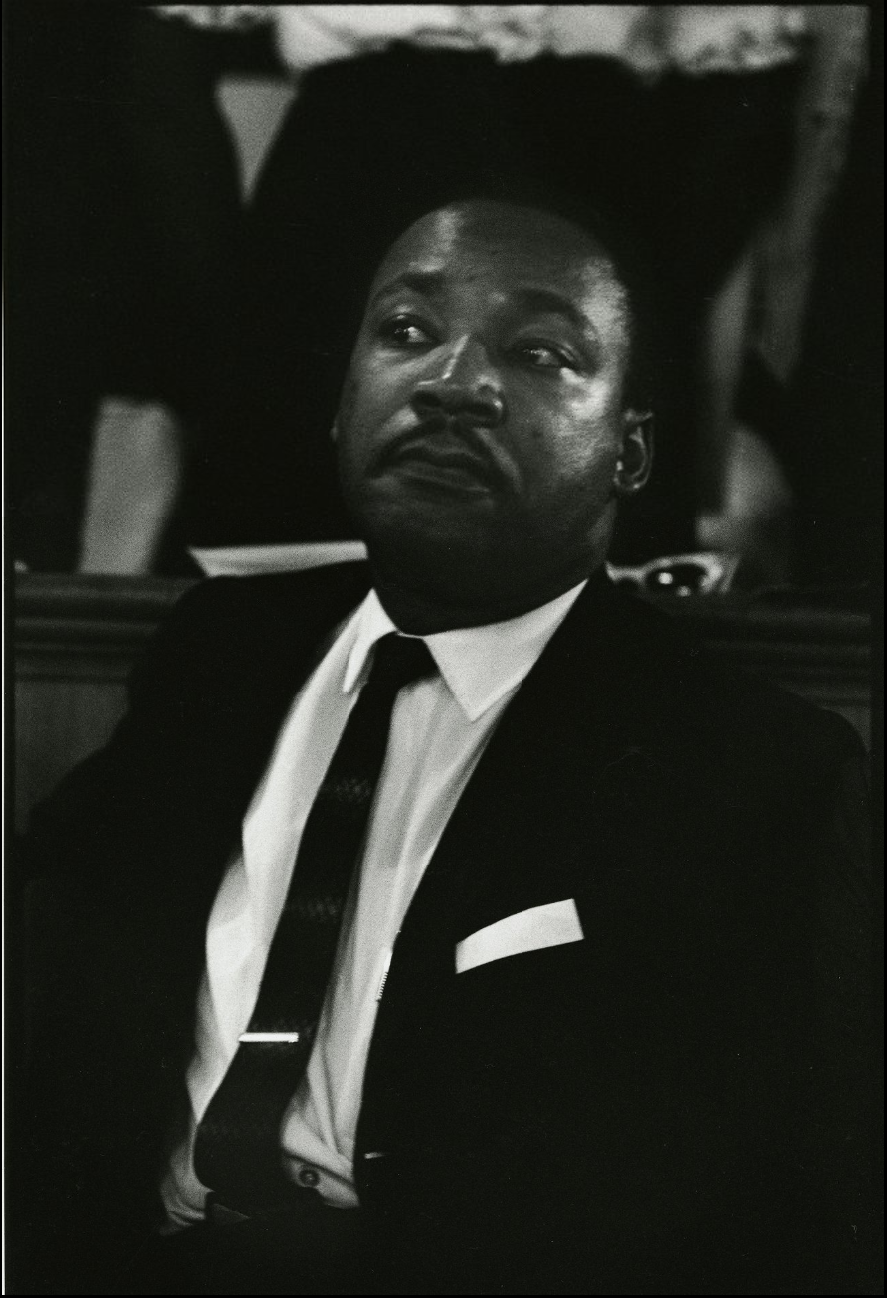

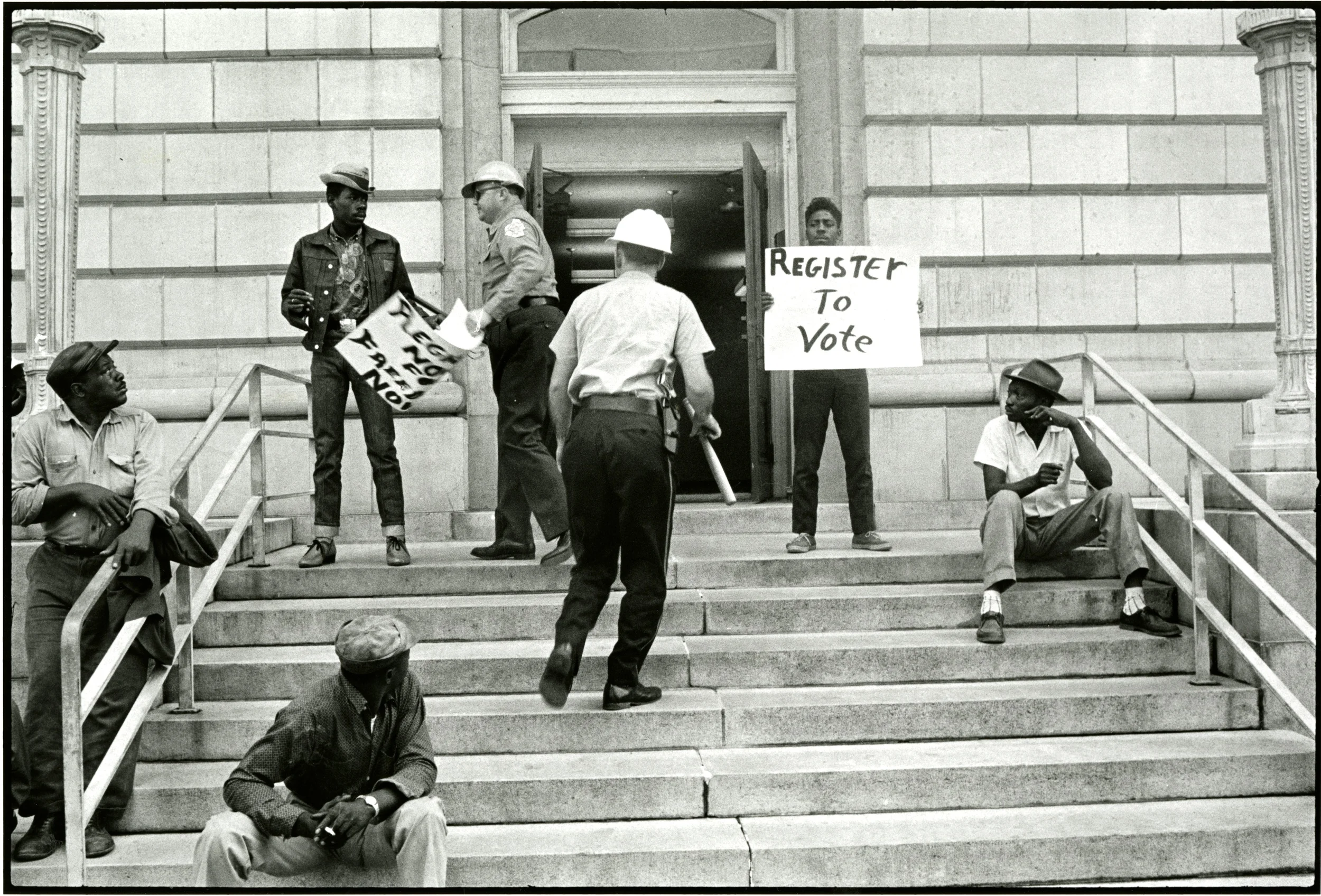

By October of 1963, Lyon found himself in Selma, Alabama, working with SNCC to organize a Freedom Day on October 7th, where scores of disenfranchised citizens demonstrated for their right to register to vote. Voting rights had been a central aim of SNCC since its founding two years earlier, but the fight had never become easier. Here, demonstrators and allies, including historian Howard Zinn, supported registration efforts even as the sheriff’s office prepared to make arrests.

Freedom Day in Selma, Alabama marked a somber tribute to the civil rights movement in the south. The day’s events were organized around efforts to register African Americans to vote in public elections, while several important cultural and political figures gave speeches and performed for the assembled crowds, including the author James Baldwin.

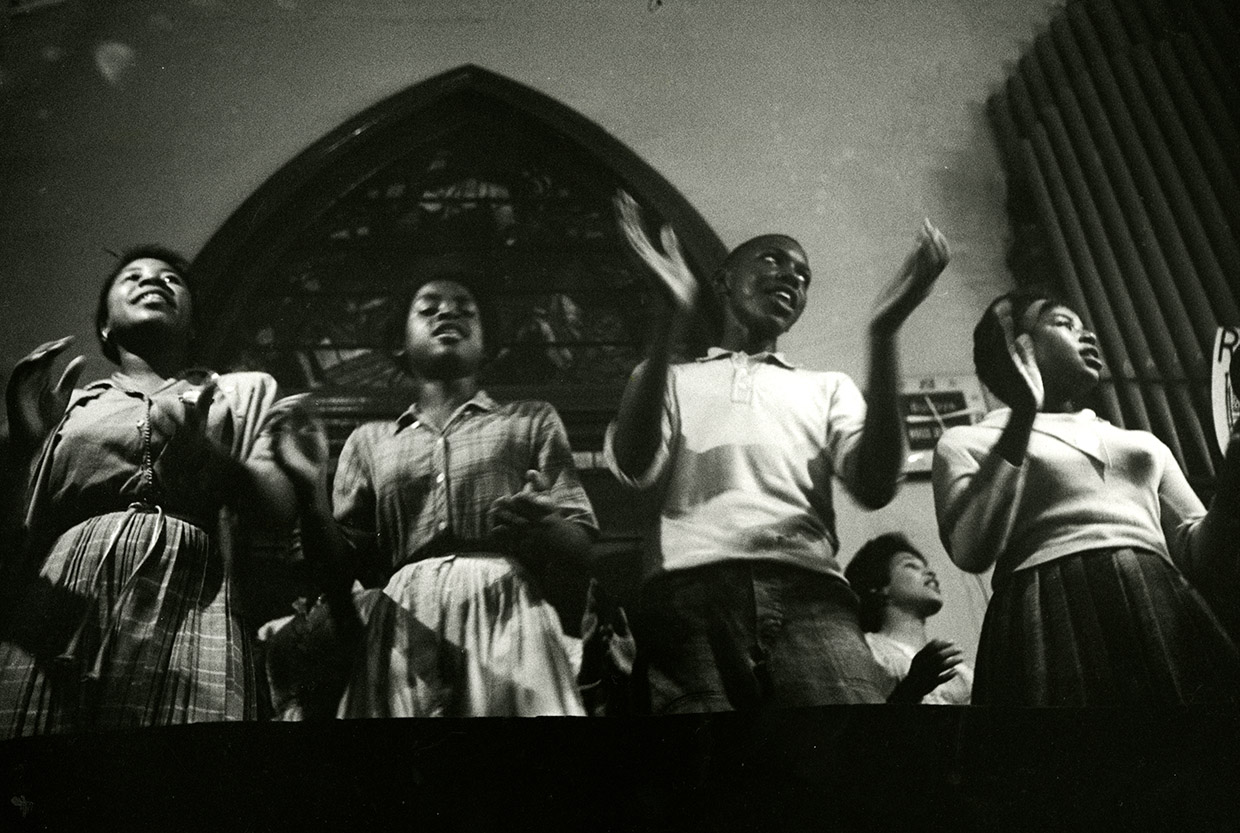

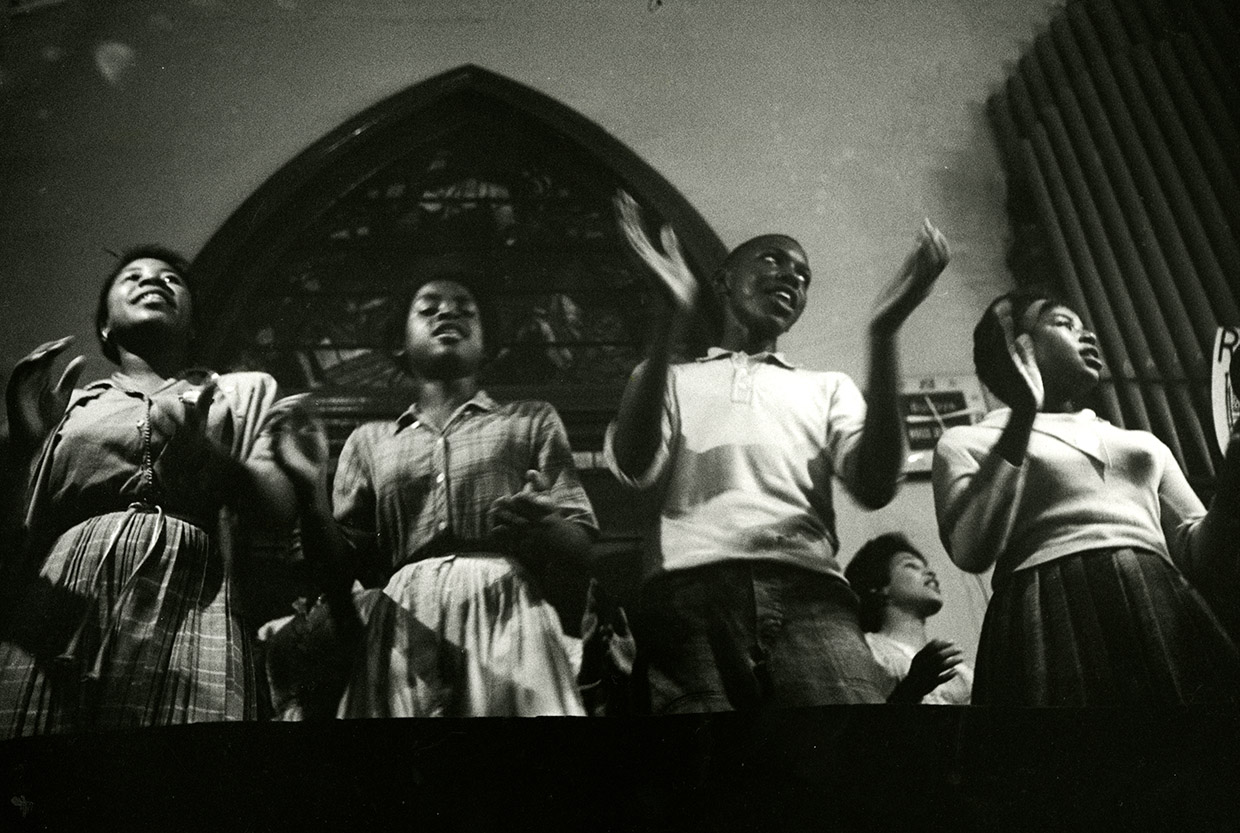

Music played a huge role in rallying the call for human rights, uniting civil rights protestors and allies through song. Along with the famous “We Shall Overcome,” many demonstrators frequently sang gospel anthems including “This Little Light of Mine.” Students from the Freedom Choir at the Tabernacle Baptist Church recorded a version of ”This Little Light of Mine” that would become a major theme for the movement in Selma.

The rest of 1963 saw Lyon travelling through the more rural south to document the voting registration efforts by SNCC chapters in Mississippi. These journeys revealed the ongoing tensions left unresolved in small towns and cities more isolated from national conversations on racial justice. In capturing this photograph, Lyon encountered several off-duty Clarksdale, Mississippi police officers whose reception and attitude of SNCC demonstrators and allies is clearly expressed in their leering gestures towards the camera.

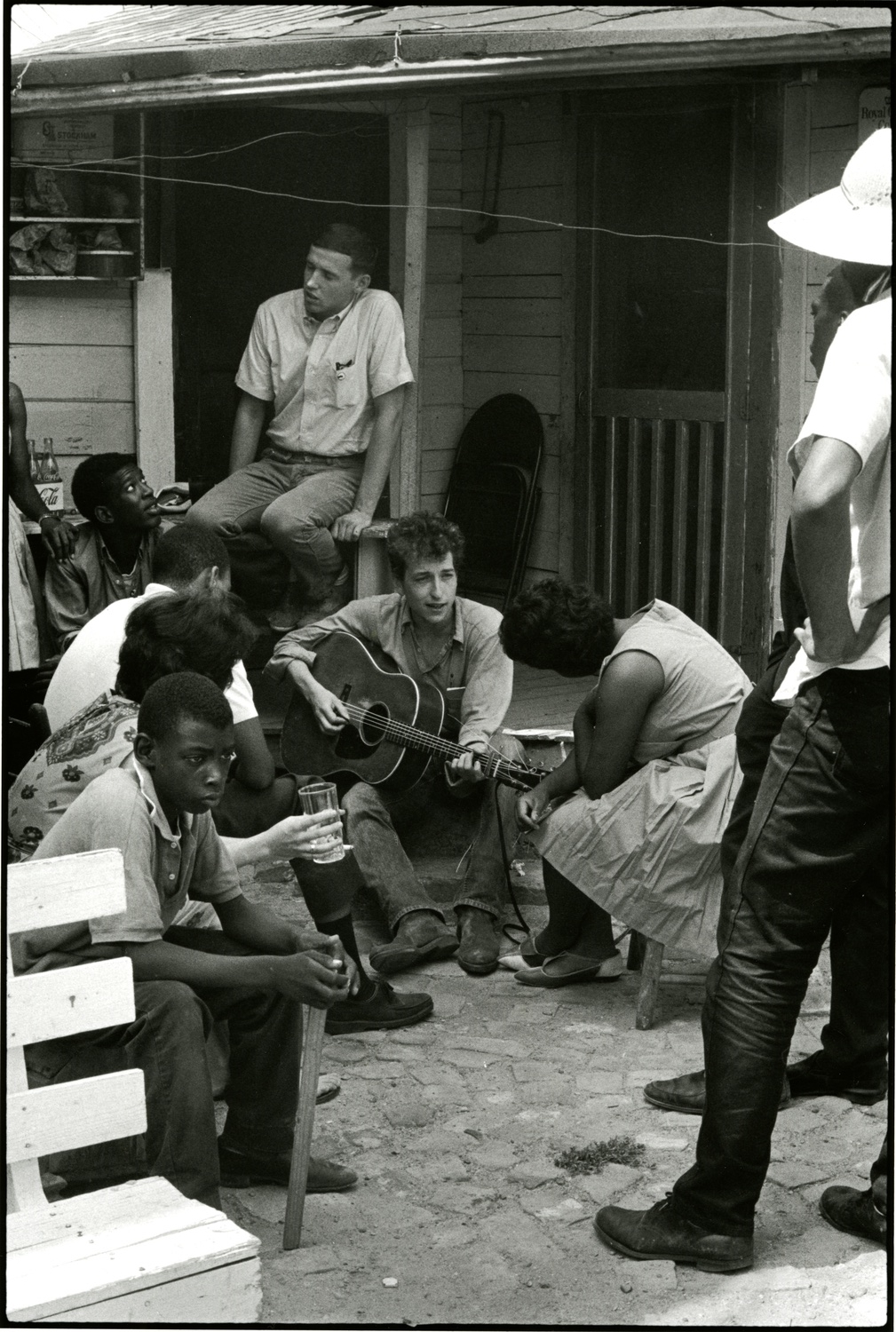

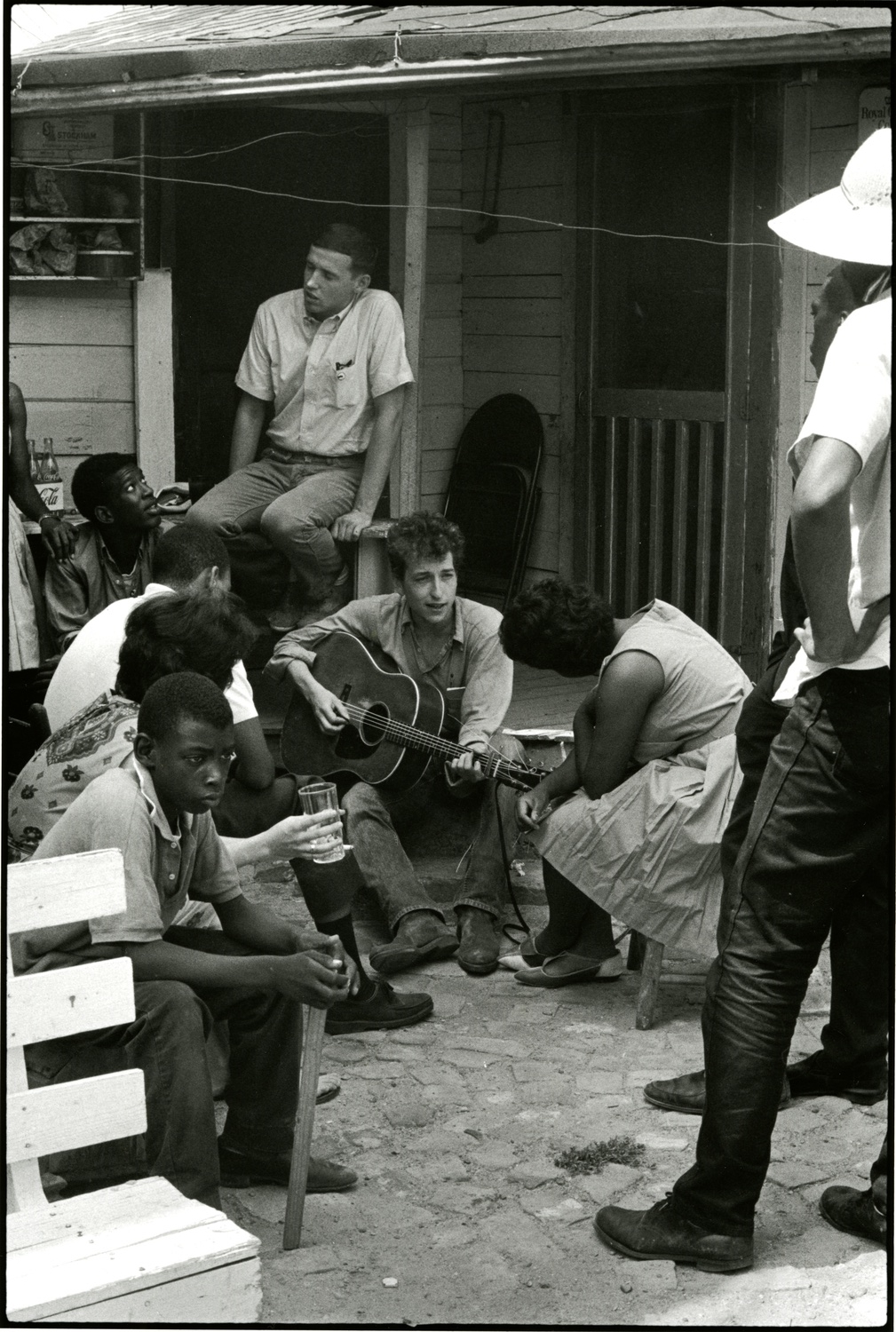

Lyon also encountered many other allies of the movement during his time in rural Mississippi. Celebrities and prominent figures such as Bob Dylan, pictured here singing with SNCC members outside a local , would often travel south in support of the efforts to rally the community for voting registration and desegregation. It was also in Mississippi that Lyon would become better acquainted with the important SNCC leader Bob Moses, who he recalled describing this period of the movement as “a tremor in the middle of the iceberg—from a stone the builders rejected.” As Lyon explained, “The presence of young, black civil rights workers in the Deep and rural South had electrified communities.”

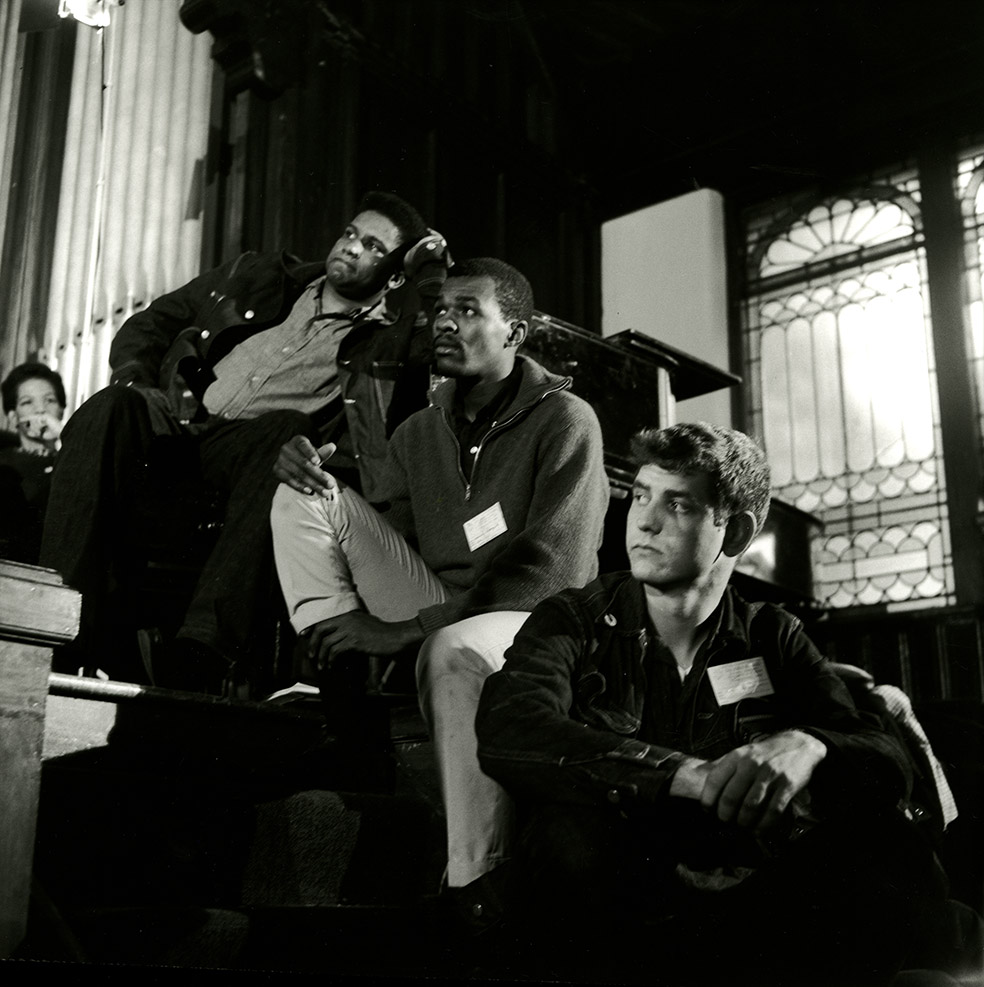

As news of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination spread across the country, SNCC leaders and organizers, including Ruby Doris Smith, James Forman, Marion Barry, and Sam Shirah assembled in various offices and chapters to determine what could happen to the organization and what their response should be. Here, the group listens for more news at a SNCC conference in Washington, D.C.

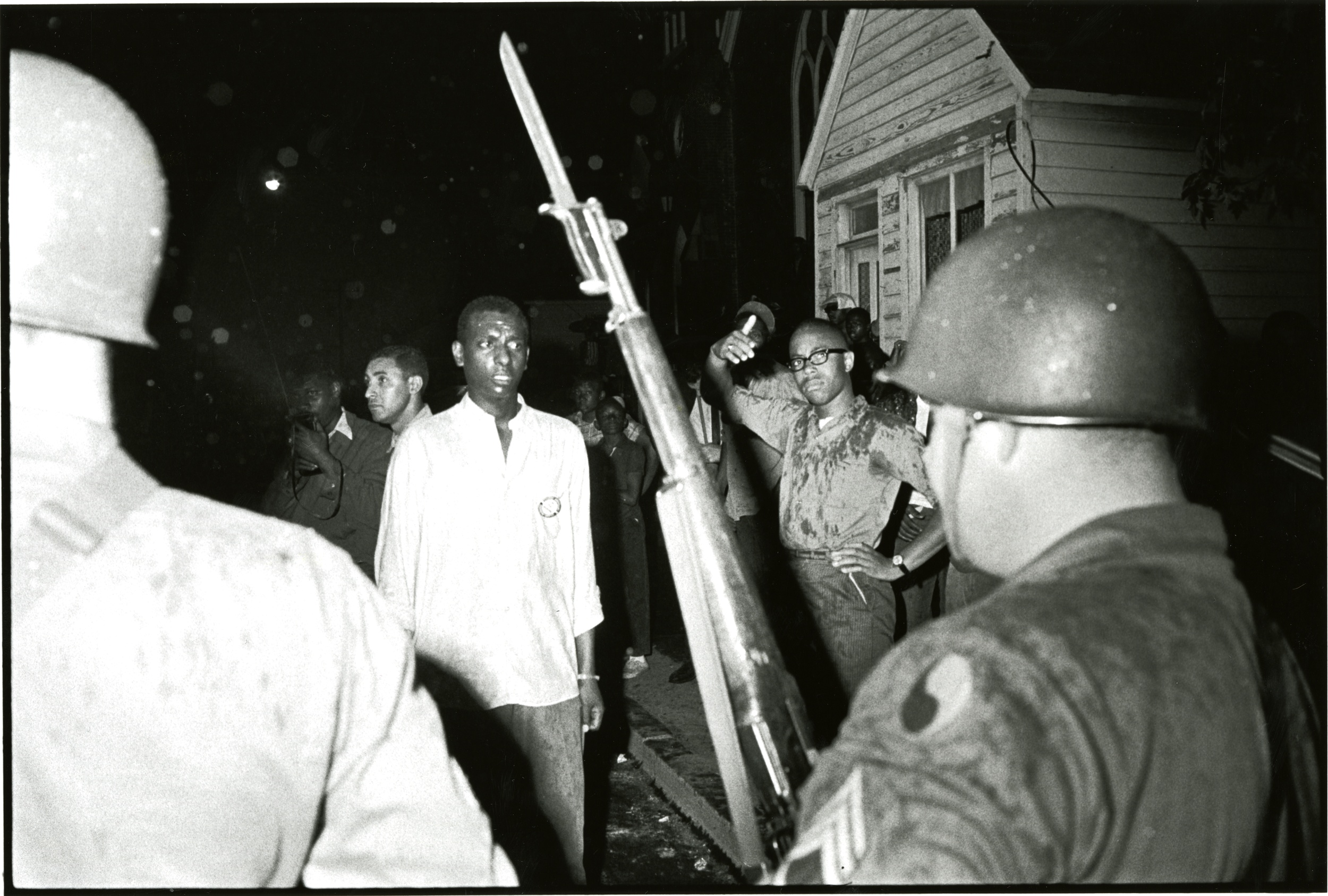

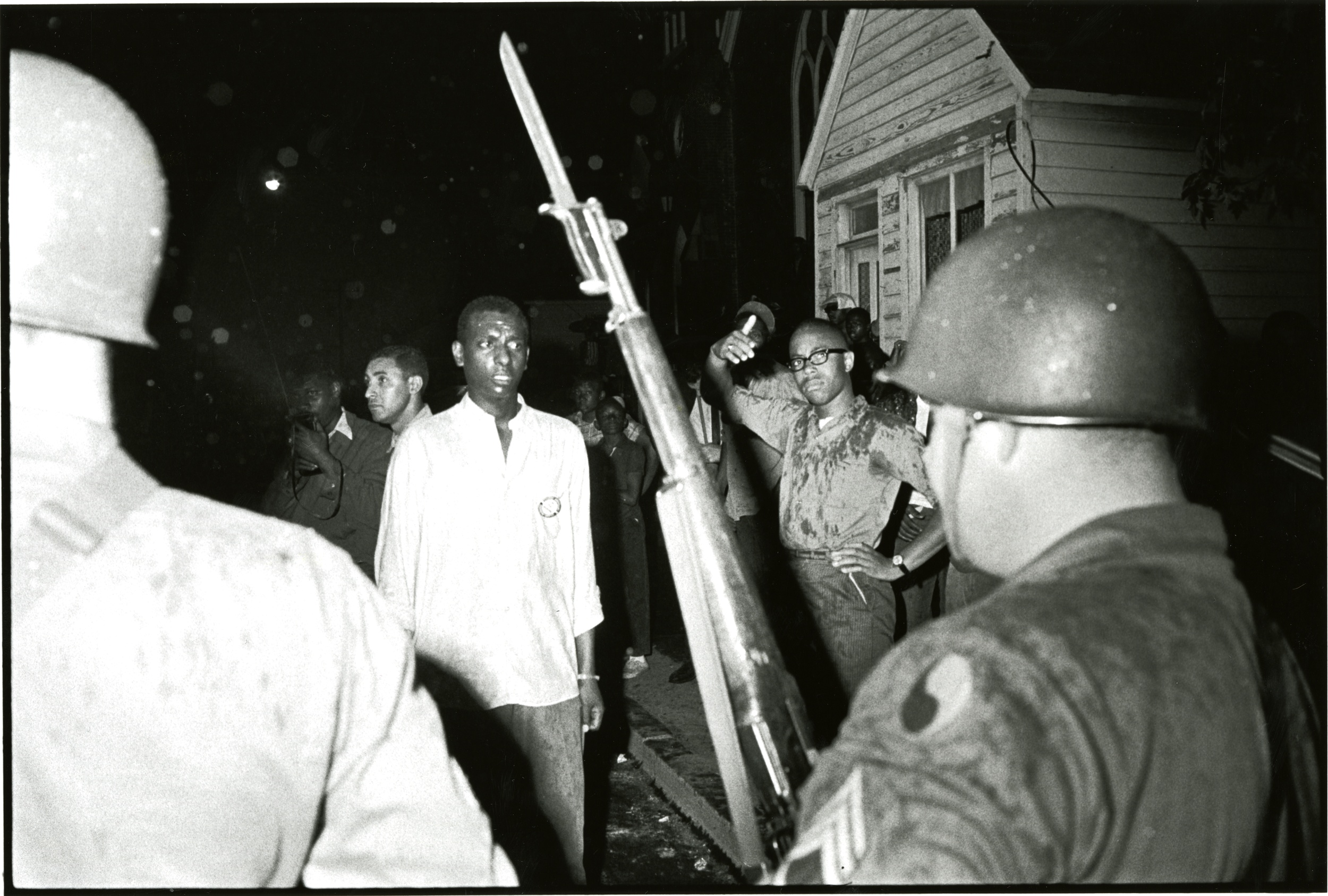

The year 1964 was a turbulent one for SNCC. The southern civil rights movement sparked conversations between members that reflected an emerging internal divide between what and who the organization represented. Lyon, already feeling the stress of an increasingly fractured organization, made one of his last trips to Cambridge, Maryland in the spring of 1964, where he witnessed a violent confrontation between police and protestors during a demonstration march in the city. Caught in the crossfire of tear gas and hurled objects, Lyon managed to capture a few profoundly tense moments, including this image of a young Stokely Carmichael angrily confronting the Maryland National Guard moments before being assaulted himself.

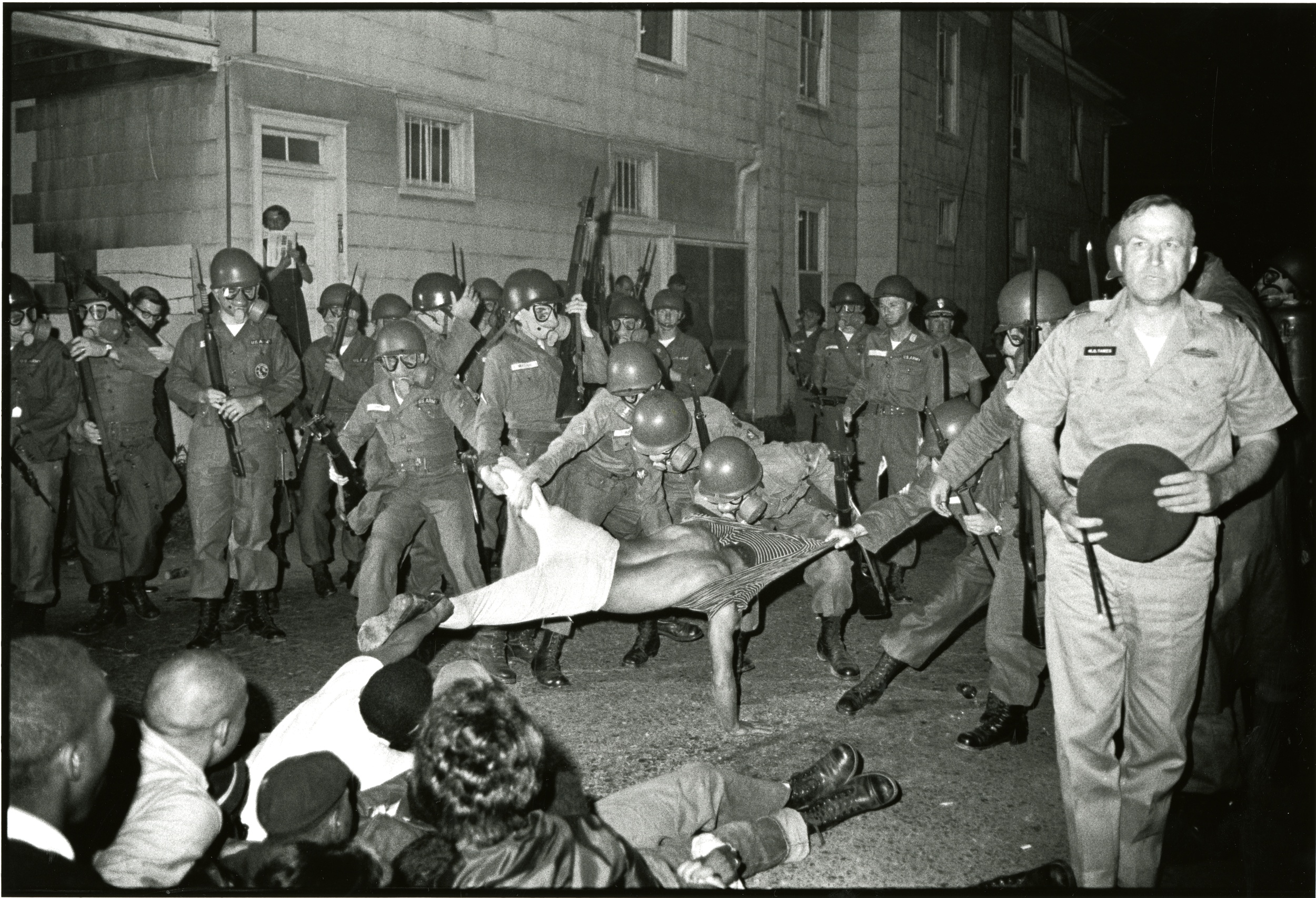

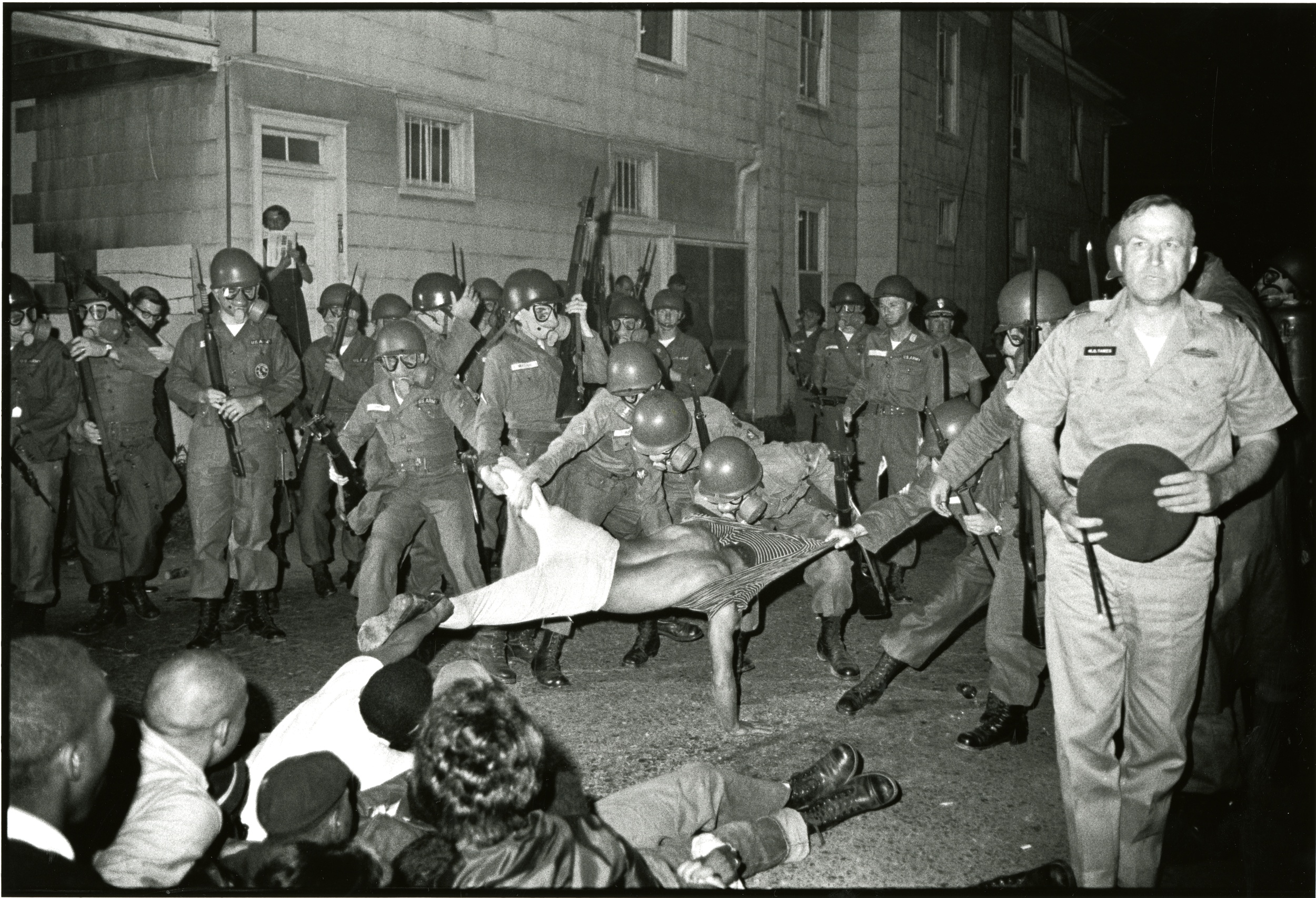

By this point, SNCC had grown large enough that Lyon was no longer the only staff photographer. One of these new photographers was Clifford Vaughs, a young African American man from California, who handed his camera to Lyon shortly before being arrested. Lyon captured the tug-of-war that followed when SNCC members tried to stop the police from taking Vaughs away. The ensuing confrontation attested to the demonstrators’ rejection of nonviolent protest, a turn that also reflected a shift in the movement of the late 1960s. These increasing pressures caused a divide within SNCC, too, as some who disagreed with the organization’s evolving nature came to the decision to leave the group altogether.

Lyon, too, became unsettled with his role as a white photographer-activist for an organization evolving in new directions. The summer of 1964 saw some of his last trips with SNCC, including one more journey to Mississippi as part of a Freedom Vote campaign. Over 80,000 people had registered to cast ballots in a recent Freedom Day vote, many for the first time in their lives, and SNCC helped community members establish the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and begin a voter registration movement known as Freedom Summer. The activities were a huge achievement for SNCC, but the group faced another crises when three SNCC workers were found murdered. The instability of the times catalyzed tensions within SNCC at the height of their increasingly direct action voting rights campaigns. Amid this activity and evolution of the organization, Lyon took his leave of the group shortly before national political pressure brought about the Voting Rights Act of 1965.